Français

41st Day of Solidarity of CSIA-Nitassinan

Octobre 9, 2021

Taneyulime Ludwina Pisili,

Kali’na from Guiana

Transcript, translation and photos Christine Prat, CSIA-Nitassinan

Welcome to all, thank you for being here. I’ll introduce myself: Taneyulime, Kali’na from Guïana, chairwoman of the Aukae association, which participates in the development of the Kali’na culture. I should have had a speaker today, unfortunately, I am very sorry, these are the inconveniences of live broadcasting. There were big storms yesterday in Guïana, there is very little connection, it is poorly installed, poorly managed, and unfortunately, we have trouble reaching our speakers. But I’m still going on with the ‘Indian Homes’ issue and talk to you about it today.

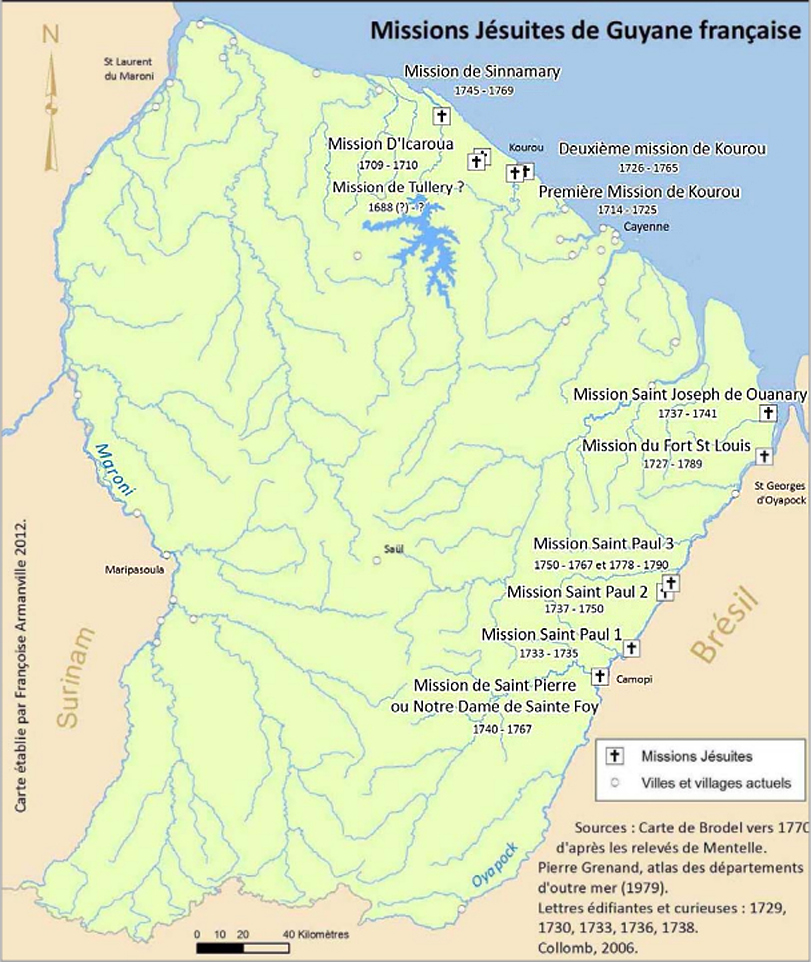

So, today, we’re going to talk about Indian ‘homes’ [boarding schools]. Maybe you have heard about them, it reminds of the news about the Canadian residential schools. You must know that in ‘France’ too, there were boarding schools for Native Americans, which contributed to the assimilation of the Indigenous populations in French Guïana, to become ‘good French’ people. Something that was initially done to make up for the school deficit. There were a lot of young Natives who could not go to school because of the environment, we are in the Amazon, there are very remote villages, and we are a population that is not originally sedentary and that moves a lot, many did not go to school. To make up for this, in the middle of the 20th century, the ‘Indian homes’ were set up. It is important to know that these Indian Boarding Schools existed from 1949 to 2012, but this process of assimilation and therefore these boarding schools have existed since the 17th century, since the arrival of the settlers in the 15th century, but especially since the 17th century, at the time of the Jesuits.

There was a desire to educate the indigenous populations, especially the Kali’na because they were mainly on the coast. [She shows a map of Guïana]. Here, there is a line that divides it in two, the coast above, and all that is Amazonian Forest, which is now the Amazonian Park. Below, you have the Wayãpi, Wayana populations, and recently, an indigenous population from Brazil that emigrates to our side, we understand why, given the current situation in Brazil and all the problems, they take refuge on French lands. And, above, on the coast, you have the Kali’na, Arawak and Teko populations. So, six indigenous populations, thirty in the past, at the beginning of colonization, and you will understand immediately that there was a big population deficit, I would speak of human genocide, and then a cultural genocide.

There was a desire to educate the indigenous populations, especially the Kali’na because they were mainly on the coast. [She shows a map of Guïana]. Here, there is a line that divides it in two, the coast above, and all that is Amazonian Forest, which is now the Amazonian Park. Below, you have the Wayãpi, Wayana populations, and recently, an indigenous population from Brazil that emigrates to our side, we understand why, given the current situation in Brazil and all the problems, they take refuge on French lands. And, above, on the coast, you have the Kali’na, Arawak and Teko populations. So, six indigenous populations, thirty in the past, at the beginning of colonization, and you will understand immediately that there was a big population deficit, I would speak of human genocide, and then a cultural genocide.

The Jesuits wanted to educate the native populations, as the Pope had decided that they could not colonize the ‘new’ lands, but that they could evangelize them. Thus, they tried to instil the Christian Word, the Catholic Word, into them, and teach them everything about the catholic religion. Those Jesuits came first, in the 17th century, as ‘saviors’, to ‘save us’ from our savagery and our lack of education. But also, thanks to the schools they created, many Kali’na escaped slavery. It is very often spoken of the enslavement of the African population, of the people deported from Africa, but WE have also known enslavement. We must not forget it, we must remember it, and, most of all, say it, denounce it. Often, Indians hunters kidnapped Indigenous populations to take them to the islands or to be slave on the spot, in Guïana. We were very far from Europe then, even more than today, and they took advantage of this situation to take us to the islands and use us as slaves. Those who have not been put in chains have been able to go to those schools, to be educated, to learn to read and write French, but also to learn certain medicinal techniques and surgery to make up for the lack of people on the land at the time and to be able to help the settler populations who lacked then – and still lack today – hospitals, services able to treat them.

The Jesuits wanted to educate the native populations, as the Pope had decided that they could not colonize the ‘new’ lands, but that they could evangelize them. Thus, they tried to instil the Christian Word, the Catholic Word, into them, and teach them everything about the catholic religion. Those Jesuits came first, in the 17th century, as ‘saviors’, to ‘save us’ from our savagery and our lack of education. But also, thanks to the schools they created, many Kali’na escaped slavery. It is very often spoken of the enslavement of the African population, of the people deported from Africa, but WE have also known enslavement. We must not forget it, we must remember it, and, most of all, say it, denounce it. Often, Indians hunters kidnapped Indigenous populations to take them to the islands or to be slave on the spot, in Guïana. We were very far from Europe then, even more than today, and they took advantage of this situation to take us to the islands and use us as slaves. Those who have not been put in chains have been able to go to those schools, to be educated, to learn to read and write French, but also to learn certain medicinal techniques and surgery to make up for the lack of people on the land at the time and to be able to help the settler populations who lacked then – and still lack today – hospitals, services able to treat them.

All of this existed, more or less, until the end of the 17th century, just before the Revolution. So, these Jesuits would be the ‘good period’ of the Indigenous boarding schools. Then there will be the ‘reductions’, that were often in Paraguay, very violent boarding schools, where assimilation is violent, hard and radical. After that, there will be a great emptiness. Anyway, it is simple, we, the indigenous populations, have never been the priority. Until today, we are not, we were already not at the time, we were very briefly, as we have seen, at the time when the Jesuits were there, but afterwards there was a total disinterest of the French administration for us. We see it in history, in 1969, it is only then that we have the right, the duty, I should say, to become French, on our papers, administratively. It is very, very late, compared to neighboring countries.

All of this existed, more or less, until the end of the 17th century, just before the Revolution. So, these Jesuits would be the ‘good period’ of the Indigenous boarding schools. Then there will be the ‘reductions’, that were often in Paraguay, very violent boarding schools, where assimilation is violent, hard and radical. After that, there will be a great emptiness. Anyway, it is simple, we, the indigenous populations, have never been the priority. Until today, we are not, we were already not at the time, we were very briefly, as we have seen, at the time when the Jesuits were there, but afterwards there was a total disinterest of the French administration for us. We see it in history, in 1969, it is only then that we have the right, the duty, I should say, to become French, on our papers, administratively. It is very, very late, compared to neighboring countries.

There is going to be a long break in history, they will totally stop being interested in us, and we are going to be decimated in a ‘microbial’ way – is it true, I don’t know, I wasn’t there – but apparently the diseases have decimated us. I think there was a small massacre, but that’s my personal opinion.

In the middle of the 20th century, there was the ‘departmentalization’ of France [‘départements’ are quite similar to counties]. So, they feel at last concerned about Guïana and the indigenous populations. And they notice indeed that all these works of assimilation and evangelization did not really work on the indigenous population of Guïana, especially among the Kali’na. Maybe you don’t know it, but we are great warriors and we have fought for a very long time. So, it is hard to assimilate us. It is also hard because we move around a lot. We tend to move around, so the people who run this country look for solutions to overcome this and how to educate these indigenous people who move around rather often, who don’t go to school, and who drop out of school, even when they do go to school, quite early, since marriages are early and their families need them for farming, fishing, etc., to sustain the family.

In the middle of the 20th century, there was the ‘departmentalization’ of France [‘départements’ are quite similar to counties]. So, they feel at last concerned about Guïana and the indigenous populations. And they notice indeed that all these works of assimilation and evangelization did not really work on the indigenous population of Guïana, especially among the Kali’na. Maybe you don’t know it, but we are great warriors and we have fought for a very long time. So, it is hard to assimilate us. It is also hard because we move around a lot. We tend to move around, so the people who run this country look for solutions to overcome this and how to educate these indigenous people who move around rather often, who don’t go to school, and who drop out of school, even when they do go to school, quite early, since marriages are early and their families need them for farming, fishing, etc., to sustain the family.

So, there were two stages. There was a first stage when the sisters came, at the beginning of the middle of the 20th century. It was called ‘orphanages’, but in fact it was clearly schools. They were places where they took Indigenous people, and took them away from their families that they still had. I don’t know if the word ‘orphanage’ is appropriate, but at least that is what they were told “we are taking you to the orphanage, because we can’t leave you like that, deep in the forest, near the rivers, etc.”. But that’s the term that the people who lived there used. And that’s how they talked about it: “I was in the orphanage”. While these people still had their parents. They were taken away from their families. They were not orphanages, it is the word these sisters used to take these children from their families, but these children still had families. Maybe their parents were away hunting, or away at sea, or away in the forest. But they still had their parents, they were effectively torn away from their parents at a very early age, since the clergy, and mainly the sisters who were there at the time, were asked to take them between the ages of 6 and 15. This was requested by decree, but it was not done in reality. Because, for them, at 6 years old they were already too old, not flexible enough, not easy to indoctrinate. So, in fact, they were taken from their parents and sent away from them, from 4 to 16 years old. The earlier the better, the younger they are, the better they are assimilated.

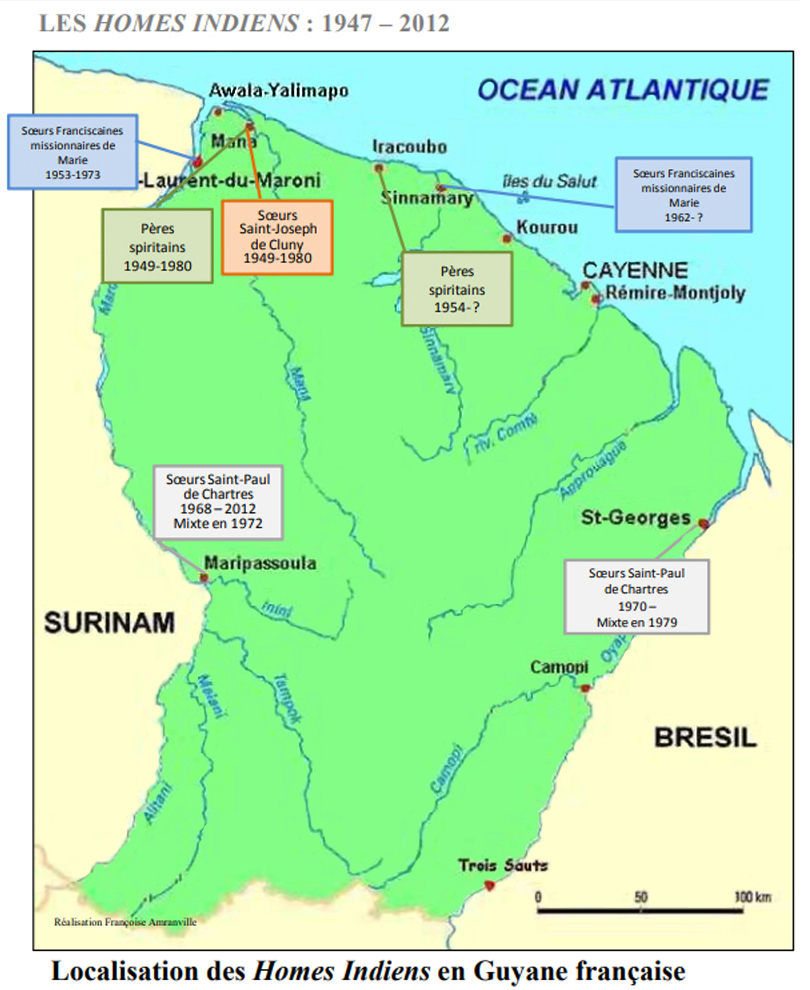

So, at the very beginning, they were sisters’ or brothers’ schools, but they were not yet ‘Indian homes’. It was made official in 1964, but we know from the archives that the reality was different, it existed since 1949. There have been five of them, mainly on the coast. As I said, by decree it was between 6 and 15 years old, but in reality, between 4 and 16 years old, to, supposedly, protect the young girls, to avoid that they are married too early, also to teach them a maximum of things and that they do not forget the good Catholic practices, since the authorities realized the multiple failures of the preceding centuries, when the Kali’na returned to their traditional customs. Thus, there were female ‘homes’ run by the Sisters and male homes run by the Brothers of the Holy Spirit. All this will last officially until 1980, but our Wayãpi and Wayana brothers will know it until 2012, when denunciations of these institutes started to be heard, institutes that ask the Kali’na – and any other Indigenous People – not to speak their mother language, to be underfed, compared to their village – while they were supposed to be saved, protected – and especially to be very far from their families, whom they can only visit once or twice a year, and they did not allow the parents to come to see their children.

So, at the very beginning, they were sisters’ or brothers’ schools, but they were not yet ‘Indian homes’. It was made official in 1964, but we know from the archives that the reality was different, it existed since 1949. There have been five of them, mainly on the coast. As I said, by decree it was between 6 and 15 years old, but in reality, between 4 and 16 years old, to, supposedly, protect the young girls, to avoid that they are married too early, also to teach them a maximum of things and that they do not forget the good Catholic practices, since the authorities realized the multiple failures of the preceding centuries, when the Kali’na returned to their traditional customs. Thus, there were female ‘homes’ run by the Sisters and male homes run by the Brothers of the Holy Spirit. All this will last officially until 1980, but our Wayãpi and Wayana brothers will know it until 2012, when denunciations of these institutes started to be heard, institutes that ask the Kali’na – and any other Indigenous People – not to speak their mother language, to be underfed, compared to their village – while they were supposed to be saved, protected – and especially to be very far from their families, whom they can only visit once or twice a year, and they did not allow the parents to come to see their children.

These institutions were made for the indigenous populations of ‘French’ Guiana. Today, I would have an indigenous person from Suriname testify, because the clergy did not stop at the borders, they went to the lands of Suriname and to the lands of Brazil to take children who were not “of the French state”, to put them in these Indian ‘homes’. They were beaten, kicked, put on slabs… Well, these are things that you could say also existed ‘at home’, in hexagonal France at that time. These are things that people from the post-war period could also tell. Indeed, it is sure. But these are things that must be emphasized and not forgotten. Taking a child away from his parents, whom he can only see twice a year, not feeding him properly, not giving him access to what the priests have access to, TV, games, not allowing him to speak his mother language with his friends, only allowing him to speak French when he is taken from Surinam where he came from schools where Dutch was spoken, it is still very complicated, it is frustrating. As in many boarding schools of this type, there is also abuse other than psychological, physical and sometimes sexual, as in many stories of catholic boarding schools. Unfortunately, we don’t have any testimony from this person, but I hope that another time you will be able to see her, and we have her story in Aukae, so we will be able to broadcast it. I think it’s important today to talk to you about this. [She shows a map] You can see the different ‘Indian homes’ in Guiana, there were mainly five, but you can see others.

I am perhaps not the best person, not having lived it, to share what it could be emotionally distressing to be in these ‘homes’, but I denounce it. It also existed in France. It existed from 1949 to 2012, but it existed for centuries too, as it is since the arrival of the colonists that they try to arrest the uneducated savages, that they try to educate them under multiple pretexts, but in the end, they don’t give them the same possibilities as other people. By mistreating them and creating this assimilation, there has been a lot of frustration among the Indigenous populations. Now, on the other hand, this is my testimony. There are people who, after these ‘homes’, did not want to teach their children to speak Kali’na, for example – I am Kali’na, so I can speak about it – there are people who did not want to teach their children to speak their mother language, because they were ashamed! There are people, until today, who are traumatized, who don’t talk about it anymore, these people are traumatized even if they don’t talk about it. Today, fortunately, we are in a cultural reappropriation. [She shows two photos of boarding schools from the past] You can see young Kali’na girls in traditional dress, who were taken away from their families, and there you can see how they were assimilated by forcing them to put on ‘civilized’ clothes.

I thank people like Ludovic Pierre, who is at the origin of the Makan collective, which for more than a year has been bringing together young activists like me, like my friend Taina who is in the audience, and like my other friend who is not here, but who perhaps hears us, and is a Kali’na artist. There is a desire, in response to these ‘Indian homes’ today, for a reappropriation of identity, but also of culture, with the reappropriation of the arts, of language and of our history, too. Our history is very often erased, you will never hear about the slavery of the Amerindians in Guïana, or maybe since a very short time. But it is not talked about, we are not recognized, it is primarily Afro-descendants and not us. Even today, many things are questioned, in art or in other fields, even music.

I thank people like Ludovic Pierre, who is at the origin of the Makan collective, which for more than a year has been bringing together young activists like me, like my friend Taina who is in the audience, and like my other friend who is not here, but who perhaps hears us, and is a Kali’na artist. There is a desire, in response to these ‘Indian homes’ today, for a reappropriation of identity, but also of culture, with the reappropriation of the arts, of language and of our history, too. Our history is very often erased, you will never hear about the slavery of the Amerindians in Guïana, or maybe since a very short time. But it is not talked about, we are not recognized, it is primarily Afro-descendants and not us. Even today, many things are questioned, in art or in other fields, even music.

As if, in the end, the thousands of years we spent on these lands had been for nothing, had left no trace. So today we are trying to restore the truth and we are trying to show that we are still alive and proud to be here, proud to be on these lands, and we are protecting them in every possible way. We participate in counter-conventions, like COPs, for instance, or different seminars. We also have young artists, we will present one today, Clarisse Da Silva, who also participates in this activism through art. And so, I thank all these young people, all these people who denounce on a daily basis, who speak about the reality of things, and I thank you also for listening to us.

As if, in the end, the thousands of years we spent on these lands had been for nothing, had left no trace. So today we are trying to restore the truth and we are trying to show that we are still alive and proud to be here, proud to be on these lands, and we are protecting them in every possible way. We participate in counter-conventions, like COPs, for instance, or different seminars. We also have young artists, we will present one today, Clarisse Da Silva, who also participates in this activism through art. And so, I thank all these young people, all these people who denounce on a daily basis, who speak about the reality of things, and I thank you also for listening to us.

I talked about cultural reappropriation, identity, but also land reappropriation. Because I know that you know, perhaps, that we there is a lot about the environment, and that here too we suffer a lot, the land suffers, and it is our land, the land of our ancestors. Even if we have difficulty in reclaiming it, it is still the land of our ancestors. Our ancestors are buried in this land, they have left burial sites, they have left artifacts. We must protect it. I also denounce all these big multinationals that are installing open-pit mines and many big power plants that are damaging our ecosystem.

We talk about human genocide that is ignored, cultural genocide that I talked about a little bit, and also ecocide, nowadays. But that concerns everyone, everyone here, because we all live on the same planet and unfortunately, it is going badly. Nothing is going well anymore, we come from the Amazon, and the lung of the earth, at the moment, rejects much more CO2 than it absorbs. We must do something, we must wake up.

Our association fights for the protection of the environment but also for the influence of the arts and the Kali’na culture. So don’t hesitate to give something to continue our projects. Thank you.

COLONIALISTS WIN REFERENDUM IN KANAKY (“NOUVELLE CALEDONIE”) REPRESENTATIVE OF YOUNG KANAKS IN FRANCE SPOKE AT CSIA DAY OF SOLIDARITY

By Christine Prat, CSIA Français

November 4th, 2018

Also published on Censored News

Today, November 4th 2018, the colonialists won the referendum by which, inhabitants of Kanaky – so-called New Caledonia – had to decide for or against Independence. Supporters of colonialism won with a much fewer votes than expected. However, settlers of European origin being now in greater numbers than Indigenous people, they could still win.

A few decades ago, tensions raised, as France was encouraging massive European immigration. Violent incidents took place in the 1980s. Two agreements were signed, in Paris in 1988, and in Nouméa in 1998. This agreement decided that several referendums would be held, in which only people already living in Kanaky in 1998 and their descent could take part. However, the immigration policy had started earlier, so that settlers arrived before 1998 are more numerous than Indigenous people.

Kanaky – ‘Nouvelle Calédonie’ – is on top of the United Nations list of countries to be decolonized. However, it is one of the biggest nickel producers on earth. Indigenous people and environmentalists say that digging mines for nickel is destroying the country, which is home to rare species, to exceptional fauna and flora. Those who oppose independence claim that, if France pulled out, the country would necessarily fall under Chinese influence. But this would mean that the world and Kanaky would remain submitted to capitalism, that will go on exploiting nickel until the land is totally destroyed.

On October 13th 2018, a delegation of young Kanaks, led by Yvannick Waikata, spoke person for the Young Kanaks Movement in France, was invited to the Annual Day of Solidarity organized by CSIA-nitassinan, the French Committee for Solidarity with Indians of the Americas. This year, Native Americans from the USA, Chili, Argentina and “French” Guyana were speakers at the event.

On October 13th 2018, a delegation of young Kanaks, led by Yvannick Waikata, spoke person for the Young Kanaks Movement in France, was invited to the Annual Day of Solidarity organized by CSIA-nitassinan, the French Committee for Solidarity with Indians of the Americas. This year, Native Americans from the USA, Chili, Argentina and “French” Guyana were speakers at the event.

The Young Kanaks offered a traditional dance to welcome the Indigenous guests from the Americas.

The Young Kanaks offered a traditional dance to welcome the Indigenous guests from the Americas.

Yvannick first explained the meaning of the dance. He said the purpose was to bow before the guests and audience, as, in their country, doors are low so that they must bow to enter someone’s house. Bowing also means that they apologize as they are going to make noise. Originally, the purpose of the dance is to initiate young men to the art of war. It is also meant to show ‘their face’. Thus, the purpose of this dance was to show ‘their face’, their identity, for which they have been struggling since 1853. Yvannick said “since that old cloth is flown above our stone (Kanaky), the flag of that colonial empire”.

Yvannick spoke for the Young Kanaks in France. He spoke about the referendum that was to take place on November 4th, explaining: “Why a self-determination referendum? Because we are in a situation of colonizer to colonized. Those who will take part in this referendum are the colonized, us, the Kanaks. ‘Kanak’ is a Hawaiian word meaning ‘human being’.”

Then he went on summing up their history: the colonial conquest began in Tasmania, and in Hawaii. The French colonial empire started in “New Caledonia”, an island thus named by James Cook in 1774. The French conquered it in 1853. The goal was, ultimately, the end of the Kanak People.

This is because of the denial of the Kanak People that they danced that day. “… when we dance somewhere, it is to show our identity, and that we are still alive”. Since 1774 and 1853, and later the policy of European immigration, the French have been trying to drown the Indigenous claim. So, they dance, to say they are still there, they still exist.

This is because of the denial of the Kanak People that they danced that day. “… when we dance somewhere, it is to show our identity, and that we are still alive”. Since 1774 and 1853, and later the policy of European immigration, the French have been trying to drown the Indigenous claim. So, they dance, to say they are still there, they still exist.

Yvannick reminded the audience that the murdered leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, had organized the Festival ‘Melanesia 2000’. For that festival, the Indigenous people decided that they would no longer limit their sacred dances and cultural practices to ceremonies, but that they would show them publicly to affirm their existence. They wanted to break completely with what had been shown in France before, during ‘colonial exhibitions’. He stressed that it was important for them to dance in Paris before the referendum, to show their faces, their culture, their identity and their history. “Our history does not start with French colonization”. So, since ‘Melanesia 2000’, their struggle was “to place the Kanak claim for identity, the cultural field, into the political field”.

Yvannick reminded the audience that the murdered leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou, had organized the Festival ‘Melanesia 2000’. For that festival, the Indigenous people decided that they would no longer limit their sacred dances and cultural practices to ceremonies, but that they would show them publicly to affirm their existence. They wanted to break completely with what had been shown in France before, during ‘colonial exhibitions’. He stressed that it was important for them to dance in Paris before the referendum, to show their faces, their culture, their identity and their history. “Our history does not start with French colonization”. So, since ‘Melanesia 2000’, their struggle was “to place the Kanak claim for identity, the cultural field, into the political field”.

After that summary of the history from the 1980s to today, Yvannick said “We, the young people, are the generation born from those peace agreements. There have been two agreements, that of Matignon in 1988 et that of Nouméa in 1998. We are the generation that lived through that peace. For the November 4 referendum, the Young Kanaks Movement creates spaces to speak, to awake the awareness among our people. Of course, we did not live the civil war situation in ‘Nouvelle Calédonie’, those ‘events’, as historians put it, but it was a war, it actually was an independence war”.

The Young Kanaks Movement works to awake awareness about the Kanak People history, in particular that of the heroes of the struggle, as the French National Education does not do anything, does not even mention the Kanak People.

What the Young Kanaks Movement wants is an identity revival. Yvannick says “for us, it is important that you can identify us and see who we are. Not reduce us to what colonial exhibitions produced in the collective imagination of the French People. So, it is important to dance and show our culture. To come nearer, to learn to know each other. We do not blame the French People at all, we blame the colonial administration.” He added “you are also human beings, like us, so we can reach you”. The colonial exhibitions created an imaginary Other, supposed to be a savage. “At the last colonial exhibition, there was Christian Karembeu’s – star of the French National Football Team – grandfather. His grandfather was a school master in “Nouvelle Calédonie”, but he came here to impersonate a savage!”

What the Young Kanaks Movement wants is an identity revival. Yvannick says “for us, it is important that you can identify us and see who we are. Not reduce us to what colonial exhibitions produced in the collective imagination of the French People. So, it is important to dance and show our culture. To come nearer, to learn to know each other. We do not blame the French People at all, we blame the colonial administration.” He added “you are also human beings, like us, so we can reach you”. The colonial exhibitions created an imaginary Other, supposed to be a savage. “At the last colonial exhibition, there was Christian Karembeu’s – star of the French National Football Team – grandfather. His grandfather was a school master in “Nouvelle Calédonie”, but he came here to impersonate a savage!”

“When we come to dance here, it is to decolonize ourselves. The message we bring is to learn to know each other, through the Kanak People’s struggle. I want to thank you for being here and I hope we shall remain connected. We still need you, we still need solidarity. Thank you.”