Hartman Deetz is from Mashpee, a member of the Wampanoag tribe. He has been involved in Indigenous and Environmental movements for over 20 years. His activism mainly relies on his spirituality and his Indigenous traditions, that are based on the idea that the Earth is a living being and that it is necessary never to forget it. He has been taking part in ceremonies ever since he was 12. He has worked with the Mashpee Coalition for Native Action, took part in the Long Walk in 2008 and Idle No More in San Francisco. He has been in Standing Rock and in Indian Bayou, Louisiana, to struggle against pipelines projects that threaten the Mississippi river. He is also involved in a struggle to have the Sword removed from the Massachusetts’s flag and in another campaign aiming to have the Mashpee Reservation Act be fully implemented. Hartman is also an artist and jewelry designer.

Hartman Deetz Français

October 12, 2019

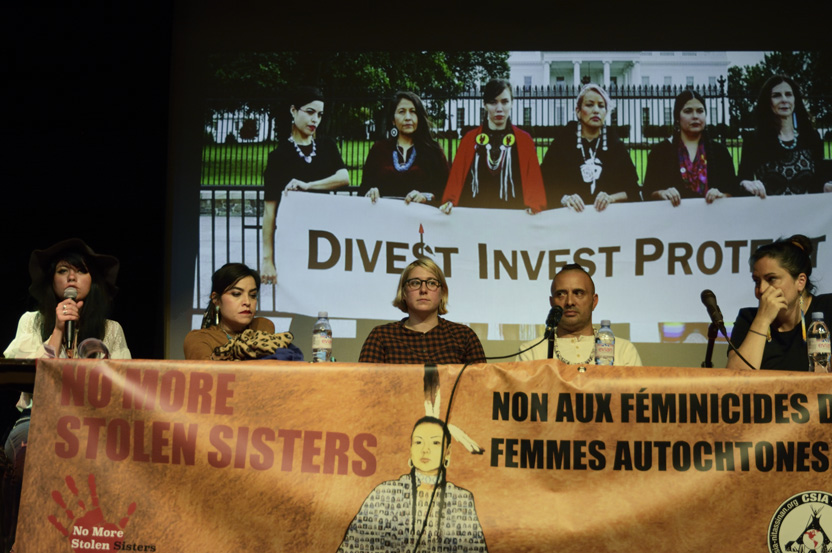

CSIA, Annual Day of Solidarity

Transcript and photos Christine Prat, CSIA

Hartman Deetz: Bonjour. [He presents himself in his own language]. Good evening. My name is Hartman Deetz, I am from Mashpee and a Wampanoag. I think the easiest is to talk about the campaigns I am working on: the state flag, and the Mashpee Reservation Reaffirmation Act. These issues can be interconnected, as many things in this world can be interconnected.

Hartman Deetz: Bonjour. [He presents himself in his own language]. Good evening. My name is Hartman Deetz, I am from Mashpee and a Wampanoag. I think the easiest is to talk about the campaigns I am working on: the state flag, and the Mashpee Reservation Reaffirmation Act. These issues can be interconnected, as many things in this world can be interconnected.

We are going to deal with some history, as most Native issues have their roots and their origins in history. Many of the wrongs done to people in the Americas, have their origins hundreds of years back. We only in recent decades started to talk about and address that these things are wrong.

I am going to address the audience. By showing hands, who has ever heard of the Wampanoag? A few. Then I am going to ask by showing hands, who has ever heard of the American Thanks Giving?

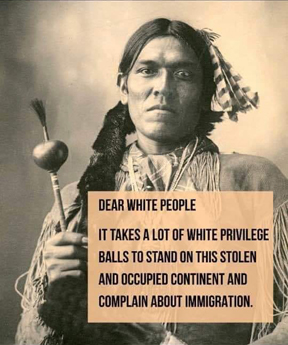

We are commonly known as the Indians, the Pilgrims and the Indians. We are “the Indians”. But we never get our own name. So, to understand what we are dealing with as Wampanoag people, we are in our original homelands, something that is not the case for many Indigenous Peoples in the Americas. My father has two acres of land, never owned by a White man ever. This is significant. In spite of this, it was not until the year 2007 that the United States Government acknowledged my People as an Indigenous Tribe. And now, they are seeking to take the last 1%, less than 1%, of our land away, in a reversal of the Trump Administration. To understand part of the situation, we have to look back to the 1600’s. We signed the 1621 Agreement with the English colonists. It said they would respect their laws and we would respect our laws, and if our folks broke our laws they would be punished by our folks, and if theirs broke their laws, they would be punished by their folks, in their jurisdiction. This treaty lasted three years. This is why the celebration of the day talks about the American origins. The Indians and the Pilgrims.

We are commonly known as the Indians, the Pilgrims and the Indians. We are “the Indians”. But we never get our own name. So, to understand what we are dealing with as Wampanoag people, we are in our original homelands, something that is not the case for many Indigenous Peoples in the Americas. My father has two acres of land, never owned by a White man ever. This is significant. In spite of this, it was not until the year 2007 that the United States Government acknowledged my People as an Indigenous Tribe. And now, they are seeking to take the last 1%, less than 1%, of our land away, in a reversal of the Trump Administration. To understand part of the situation, we have to look back to the 1600’s. We signed the 1621 Agreement with the English colonists. It said they would respect their laws and we would respect our laws, and if our folks broke our laws they would be punished by our folks, and if theirs broke their laws, they would be punished by their folks, in their jurisdiction. This treaty lasted three years. This is why the celebration of the day talks about the American origins. The Indians and the Pilgrims.

The English folks would not deal with our women leaders. They wanted our women to send their sons, to send their brothers, to send their husbands to speak for them. We had a powerful Queen, Weetamoo, she controlled vast territories of land. The English folks made many attempts to get this land from under her feet. They tried to buy it from her sons, from her brothers. They got some of her male relatives to agree to sell. These cases were brought into the court systems, where the leadership acknowledged that only she had a claim to that land and no one else, and the right to sell it. In spite of that, the deeds were recognized by the English court system and confirmed. This sparked a war known as King Philip’s War. They named this war King Philip’s War, because the man on whom they placed the responsibility for the war, they chose to call Philip. Because they refused to bother to learn to pronounce his own name, Metacom. This war was a very violent war, the most violent war fought on New-England soil. Entire villages and towns were destroyed on both sides. And, as a conclusion of that war – we had, as Native people, allies, including the Abenaki folks – they started to sue for peace and strike treaties on victors’ terms, to return to the planting grounds and start planting in the spring again. And as people returned to their open spaces, came out of their fortresses, they were attacked. Weetamoo was killed and her body thrown in the river. Philip, Metacom, was killed in the swamps. And his head cut off and stuck on a pike. It was displayed in the center of Plymouth colony for over fifty years. And now, the flag of Massachusetts bears a sword above the head of a Native man, with the word ‘By the sword we seek peace’.

The English folks would not deal with our women leaders. They wanted our women to send their sons, to send their brothers, to send their husbands to speak for them. We had a powerful Queen, Weetamoo, she controlled vast territories of land. The English folks made many attempts to get this land from under her feet. They tried to buy it from her sons, from her brothers. They got some of her male relatives to agree to sell. These cases were brought into the court systems, where the leadership acknowledged that only she had a claim to that land and no one else, and the right to sell it. In spite of that, the deeds were recognized by the English court system and confirmed. This sparked a war known as King Philip’s War. They named this war King Philip’s War, because the man on whom they placed the responsibility for the war, they chose to call Philip. Because they refused to bother to learn to pronounce his own name, Metacom. This war was a very violent war, the most violent war fought on New-England soil. Entire villages and towns were destroyed on both sides. And, as a conclusion of that war – we had, as Native people, allies, including the Abenaki folks – they started to sue for peace and strike treaties on victors’ terms, to return to the planting grounds and start planting in the spring again. And as people returned to their open spaces, came out of their fortresses, they were attacked. Weetamoo was killed and her body thrown in the river. Philip, Metacom, was killed in the swamps. And his head cut off and stuck on a pike. It was displayed in the center of Plymouth colony for over fifty years. And now, the flag of Massachusetts bears a sword above the head of a Native man, with the word ‘By the sword we seek peace’.

In 2018, 150 acres, in the very place where Weetamoo’s landholdings were, the center of the lands that sparked the war of King Philip’s War, became the sticking point as they chose to use this land to reverse the decision on our acknowledgement of being a Native People, of being a tribe, of being sovereign. They said we have no connection to that land historically. This is the justification they use now to strip us of our inherent right on the last less than 1% of our land.

My tribe, my community has about 3000 people, and about 300 acres. That’s about 400 m² in one acre. We have about 10 people per acre. How are we expected to continue to exist as Wampanoag people in our own land? If we don’t have a place to be? How can we be Mashpee people, if we are not next to the Mashpee pond? How can we be Mashpee people, if we are not able to get to the Mashpee river? These bodies of water define us. They are what give us our identity as Mashpee people. We are faced with very dire need to see some justice. We have been struggling for hundreds of years, through changes of laws, through England, through the American Revolution. Under England, we were praying towns, the American Revolution came and we became Indian Districts, and then we were incorporated into a town, an official town, and then recognized as a state tribe, and then eventually recognized as a Federal Tribe. And now, they have changed the rules once again. For the United States, we are Indians when it suits them. And we are not when it does not. So, we are hoping to see some pressure from the world, to get the United States to acknowledge the Rights of the Native Peoples that they celebrate every November, in their creation myth, to have a place to be and exist.

My tribe, my community has about 3000 people, and about 300 acres. That’s about 400 m² in one acre. We have about 10 people per acre. How are we expected to continue to exist as Wampanoag people in our own land? If we don’t have a place to be? How can we be Mashpee people, if we are not next to the Mashpee pond? How can we be Mashpee people, if we are not able to get to the Mashpee river? These bodies of water define us. They are what give us our identity as Mashpee people. We are faced with very dire need to see some justice. We have been struggling for hundreds of years, through changes of laws, through England, through the American Revolution. Under England, we were praying towns, the American Revolution came and we became Indian Districts, and then we were incorporated into a town, an official town, and then recognized as a state tribe, and then eventually recognized as a Federal Tribe. And now, they have changed the rules once again. For the United States, we are Indians when it suits them. And we are not when it does not. So, we are hoping to see some pressure from the world, to get the United States to acknowledge the Rights of the Native Peoples that they celebrate every November, in their creation myth, to have a place to be and exist.