Origineel artikel in het Nederlands: click hier

et traduction française

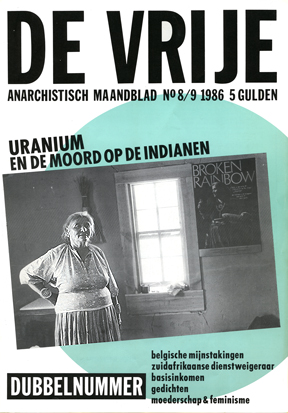

COAL, URANIUM AND THE MURDER OF THE INDIANS

From “De Vrije”, article by Jansen, Amsterdam September 1986

Translation by Christine Prat

‘The earth and I are one soul.’ This Indian saying expresses tersely what the traditional Navajos and Hopis have been trying for twelve years to make clear to the American government. The impending deportation of ten thousand Navajos from the area in Arizona where their ancestors have been living for centuries – a deportation which could begin at any moment, as the ultimatum expired on the 7th of July of this year – threatens to be an all-time low in the history of the USA. A history in which the government systematically tried to put an end to the existence of Indian cultures. In which the ‘Ancient Peoples’ had to lose out to coal and uranium mining corporations, Mormonism, politicians en ‘economical development’. This article sheds light on the background of the conflict in Arizona and describes the struggle of the traditional Navajos and Hopis against the violation of their earth and their life.

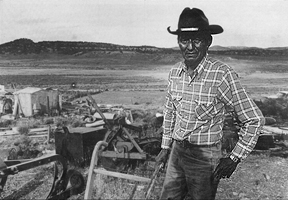

On one day in the fall of 1977 a building team from the government arrived at Black Mesa, in the heart of the Navajo reservation in Arizona. Their assignment was to place a barbed wire fence through the rocky desert. Shortly after their arrival they suddenly stood face to face with Pauline Whitesinger, a 43 years old Navajo widow and mother. Pauline ordered the men to disappear from her land. The foreman of the team answered with an obscenity. Pauline waved her fist and the next moment the foreman was lying on the ground and she was pelting the team with sticks and dirt. Shrinking from her fierce attack, the men took to their heels.

Pauline Whitesinger’s action marked the beginning of a phase of actual resistance in the struggle of the Navajos to keep the land on which they had been living for centuries and to which they belonged with heart and soul. The fence – the placing of which they have been hindering since that moment – has to come there on the ground of the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement, better known as Public Law 93-531. This law has been taken by a deliberately misled Congress. PL 93-531 pretends to solve a ‘conflict’ between the Navajos and the Hopis about the ownership of the Joint Use Area, an area at their common disposal. The Navajos were supposed to have confiscated it and the Hopis to want to throw the Navajos out of it. In reality, there is no conflict. Between the Navajo People and the Hopi People, that is. The real conflict is between the traditional Navajos and Hopis on one side, and their tribal councils appointed against their will by the central government, that central government itself, a number of mining and energy corporations and the Mormon church on the other side. The interest that binds those four – often closely interwoven – entities rests in the many billions worth coal, uranium, oil and gas in the ground of the Joint Use Area. The boards of directors – dominated by Mormons – of mining and energy corporations – which are often also the property of Mormons, are impatient to conclude with each other ground exploitation contracts. However, the Indians living on that ground do not intend to sacrifice it to that purpose. Moreover, the fact that the Joint Use Area (JUA) has long been common property of the Hopis and the Navajos makes the signing of contracts more complicated. The mining and energy corporations had therefore to create the ‘conflict’ and to stage a complete war on the ground, and they ultimately got the Congress to adopt their ‘solution for the conflict between the Hopis and the Navajos’. PL 93-531 stipulates that the Joint Use Area must be divided by a barbed wire fence into a Navajo half and a Hopi half. All the Navajos who live in the from now on Hopi area – about ten thousand – must leave. The same applies to the hundred Hopis who live on the Navajo area. Most are placed outside the reservation. This way the JUA becomes, in juridical and practical terms, quite more accessible for raw materials extraction.

THE EARTH LIVES

In order to understand what is exactly going on in and around the reservations, it is important to know something of the Hopi and Navajo history and culture. The gold fever of 1848 brought a stream of white Mormons and others to Arizona and New-Mexico (among others). Many settled on the land that had belonged to the Hopis for thousand years and on the bordering area where the Navajos had been living for six hundred years. Frictions occurred. Hopi resistance traditionally consists of non-violent refusal to cooperate. But the Navajos fought back against the white intruders but were defeated. A cavalry brigade headed by America’s national hero Kit Carson burned their land, destroyed their animals and orchards and kidnapped 8500 Navajos to a concentration camp near Fort Sumner, where many died of starvation. A few years later, the government came to the conclusion that it would be economically more profitable to enable the Navajo to sustain themselves than to fight them. The survivors were released and dropped into a small, barren reservation. In between, the white people had confiscated their land, so that the Navajos who escaped from the reservation settled down in the immediate neighborhood of the Hopis. The pressure brought by their presence causes every now and then minor disputes, but they are always solved among each other. In general, the relationship between the two peoples is good. The Hopis have much more problems with the fact that the US also created a reservation for them in 1882. Something that they had absolutely no right to do according to the Hopis: according to the Guadalupe-Hidalgo treaty, they have remained an independent nation.

In 1934 the Hopi reservation is reduced to a third of its previous size. The Hopis now graze their livestock in ‘District 6’; the Navajos outside it, in the rest of the previous reservation. The property rights on this new piece of no-man’s land belong to both people jointly. This is how the Joint Use Area came into existence.

At the beginning, the American government thinks that the Hopis and the Navajos have been safely put away on a few patches of worthless land. But it soon turns out that the ground under their reservations abundantly contains oil and gas, and in the course of the twentieth century it becomes obvious that the Navajos and the Hopis sit on top of a billions worth treasure of minerals: huge coal fields and billions of tons of uranium lie under the surface. Many mining and energy corporations immediately show great interest. Their attempts to conclude ground exploitation contracts with the Indians fail, however. The latter happen to think differently about the earth than the white Americans. Although each people has its own way of life and culture – the Hopis live from agriculture on top of the rocky mesas, while the Navajos from way back move around the desert with their livestock – their attitude towards life is in fact similar. They feel inseparably bound to the land that gave birth to them and their ancestors. And the land, the earth lives. Everything that grows or moves on it has its place in her cycle; everything holds everything in balance. ‘We must see ourselves as a part of the earth, not as an enemy from outside trying to force our will upon her.’ This is the way one of the Indians expresses it. ‘We know that because we are a living part of her, we cannot damage a small piece of her without hurting ourselves.’ This is why the Ancient Peoples do not take for themselves more than what is necessary. For instance, the Hopis rarely have more animals than are necessary for their daily needs. The land itself is nobody’s property. But it is the duty of the people living on it to protect it. To tear and maim this living Mother Earth has long been unthinkable for the Hopis and the Navajos, until they saw it happen under their very eyes.

Americans and Westerners generally see the earth differently: as a consumer item appreciated basically for its exchange value. It is a matter of course to divide, buy and sell land, to break it open to get all kind of things out of it and to cover it with concrete. The land is dead material. This is the difference between the western notion of the earth and the Indian approach to it that ultimately founds the conflict about the JUA.

MORMON HELP

Apart from recalcitrant contract partners, there is also, at the beginning of the century, another obstacle in the way of the energy developers to be. With whom can they conclude an agreement? According to a 1891 law, it should happen with ‘the ruling council representing the Indians’. But such a council does not exist. Traditional Hopis and Navajos have never known anything like a central authority or representative body. The political power has been for times immemorial decentralized and relies on a consensus between autonomous communities. For the Navajos the basic political unit is the autonomous family. It includes between twenty and two hundred members who economically work together and hold their ceremonies in common. At the head can sometimes be a man, but it is usually a woman. The livestock and belongings are managed by the women, and their descent is determined by the women’s lineage. It is no coincidence that the main resistance against the consequences of PL 91-531 comes from them. It is often women over sixty, armed with riffles, who stand against the building teams.

The central authority phenomenon is alien to the Hopis as well. Each Hopi village is an autonomous unit with absolute self government. They do have a traditional leader, de Kikmongwi, but his or her authority is based solely on his or her wisdom. If there are problems, the Kikmongwis of the different villages meet to exchange information and deliberate. However, actual decisions are taken exclusively in the villages and not before all the people involved have come to an agreement. This is often a laborious way demanding a lot of talking, but consensus is a condition for decisions concerning the village.

Such an organization of Indian society was a thorn in the side of the energy corporations and the government. Not only the Indians were not adapted to American society, but it was also impossible to do business with them. Where were the people entitled to put a signature under a contract and were also ready to do it without having to get all the others to agree? Those people had to be made up. And there were, as it happens, Mormons who were already busy with it since 1880: to turn traditional Indians into profit and power thirsty American citizens. The Mormon faith teaches that a dark skin is a God punishment. The Indians are dark, according to the Book of Mormon, because they have fallen into disbelief and vanity. If they convert to Mormonism, they will turn white again. Led by the noble wish to save the Indians, the Mormons start around 1880 to drag the most gifted Hopi and Navajo children (among others) out of the reservations to send them far away to boarding schools or foster homes. Until 1915 it often happened with the help of the American cavalry who literally kidnapped children and arrested recalcitrant parents. After 1915 they mainly misused the dire financial situation of the parents to persuade them. In the mainly Mormon foster homes it is forbidden for the children to speak their own language or to wear their traditional clothes and hairstyle. They are given English names and their Indian habits are declared taboo. The children are subjected to an extensive religious indoctrination. Nowadays between twenty and forty percent of the Hopis are Mormons – among the Navajos the percentage is somewhat lower. Those people believe that God’s Realm can be realized on earth by accumulating as much as possible material richness. The Mormon church, which has millions of members, is thus very rich and powerful. Mormons own many companies and transnational corporations. In the state of Utah (which includes a portion of the Navajo reservation) they control the whole political life. They founded Salt Lake City. In the companies whose greed has been drawn to the riches of Indian ground Mormon interests are greatly represented.

Mormon Hopis and Navajos see their own land with the same eyes as those companies. This is precisely why the present ‘conflict’ can be presented as such.

“YELLOW CAKE”

Let’s go back to the beginning of the century. While the Mormons are helping Indians to become white capitalists, the BIA – a governmental institution that thinks on the same line as business men – does not remain idle. In 1921 a subsidiary of Standard Oil finds oil in the Navajo reservation. The BIA immediately convenes all Navajo men (!) to approve an oil agreement. The seventy five persons attending unanimously vote against it. The BIA feels concerned by Standard Oil’s fate. After two years of efforts they manage, probably through threats or false promises, to form a permanent Navajo Council whose first act is to hand their contracting powers over to the BIA!

This was sixty three years ago. Nowadays there are four strip coal mines (the coal is obtained by blowing up the upper layer of the land) and five huge coal power plants on the Navajo reservation. The area, which used to have the cleanest air in the USA, is now covered with black smoke and soot. The Four Corners Power Plant rejects every day three hundred fifty tons of sulfur compounds and two hundred tons of nitrogen compounds in the atmosphere. There are thirty eight uranium mines and six uranium factories. At the moment they mostly stand still because coal is easier to get and less controversial. However, uranium mining is still interesting for the production of nuclear weapons.

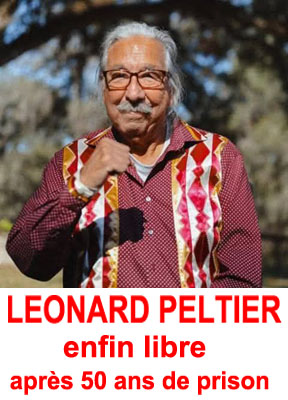

Of the five thousand Navajo miners who worked in the uranium mines between 1952 and 1969, over fourteen hundred died of cancer, mostly lung cancer. A great number of survivors suffer from it. The underground water is contaminated. Countless horses and sheep died from having drunk it. Radioactive waste has been left behind in huge heaps all over the reservation. Maria van Kints of the association Dutch Action Group for North American Indians (NANAI) has seen it herself: ‘It looks like big sand hills. Yellow Cake, they call it. The children play in it, houses are built with it, the sheep eat the grass that grows on it, so that it comes into the food chain. And it will remain contaminated for thousands of years!’ Many children are born dead or with malformations.

Moreover, the financial agreements for oil, uranium and coal concluded by the BIA for the Navajos are the worst in the world. Typically, there is a contract on land by which the Navajos get fifteen cents for a ton of coal, while on non-Indian land it is usual to pay one and half dollar – ten times more. The Navajos themselves do not have electricity.

BOYCOT OF THE REFERENDUM

For the Hopis too, an official council has been made up. To put an end to the self government of the Indian peoples the American government issued in 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). This law was cheered as a great achievement: it gave the Indians the blessings of the American political system. The constitution has just been written for them. Among others it includes a rule according to which all decisions of their councils must be approved by the central government. The Kikmongwis have been against the IRA (which had been forced upon 76 percent of the Indians) from the beginning. They boycott the referendum about it: the Hopi way to express their opposition to something. The central administration knows that very well but still decides to consider abstention as agreement. With the consequence that the Hopis are suddenly governed by a central council that can issue laws and conclude agreements with companies in the name of the whole people. The Hopi council still has an electoral base of less than ten percent. The attendance, which for long had not been enough for a quorum, was, and is still, almost entirely composed of Mormon Hopis. These so-called ‘progressive’ find councils, exploitation of the land and ‘the American way’ all wonderful and are good friends with the administration.

In 1955 the Hopi council recruited a lawyer from Salt Lake City to conduct their negotiations with the energy companies. That John Boyden, who had self arranged through the BIA the composition of the council, is a Mormon ex-archbishop. A few years later he submitted a ‘land claim’ in the name of the Hopis to the Indian Land Claims Commission, and ‘won’. According to a recent law, this did not mean that the Hopis would get their land back, as they initially believed, but only that they would get a relatively very small amount of money, from which Boyden received a substantial percentage. Until now even the members of the council have refused to take the money.

In the sixties, Boyden concluded numerous agreements with mining and energy companies. The Kikmongwis, as representatives of the traditional Hopis, have protested at every stage and even brought the case before a federal judge, who rejected their claim that the council was not a legitimate representative of their people, on the ground that they had no right to prosecute their own authority!

NATIONAL SACRIFICE AREA

Meanwhile Boyden continues. An enquiry later showed that, apart from the Hopi council, he worked at the same time for a big Mormon coal corporation, Peabody Coal Company. It is with Peabody that he signed the most important agreements in 1964 and 1966 (his own salary being one million dollars). Peabody leases hundred square miles of land on Black Mesa, which partly lies in the Joint Use Area and contains the biggest coal field in Arizona. The mines have left enormous scars on the land. Even worse is that they use for the transport of the coal – via a hundred kilometers long pipe line – until today, seven and half million liters of water each day. This is a serious threat to the agriculture and livestock breeding on which the Indians of the already quite dry region depend. ‘The pumping of such huge quantities of water from under Black Mesa will break the harmony and bring everything out of balance’ warn the Kikmongwis in 1971. Their protest concerns the whole western way of dealing with the earth and its consequences. ‘The technical developments of the white man occurred as a consequence of his lack of concern for the spiritual and for the way in which everything lives’ according to their spokesman Thomas Banyacaya. ‘If the holy land is desecrated and torn open by raw materials exploitation and other destructive practices, it will mean on longer term the biggest death march for all the peoples of the world.’

The coal field under Black Mesa – in between declared by the National Academy of Sciences ‘National sacrifice area’ – extends as far as Big Mountain, four kilometers further into the Joint Use Area. It is estimated that there lie twenty one billions tons of easily accessible coal. However, apart from Peabody, not a single mining company manages to get something of it. Neither the Hopi council nor the Navajo council (who, unlike the traditional Navajos, do not object to issuing mining permits) have the right to lease the land independently, but together they cannot agree about who gets what. Meanwhile the people who live on Big Mountain are determined to keep all the twenty one billion tons of coal inside the ground.

“GOOD INDIANS”

In the second half of the sixties, the ‘progressive’ Hopis (the Hopi council, that is) started an intensive campaign in order to split the Joint Use Area and get rid of the Navajos. They are personally concerned by the exploitation of the land, as the salary of Indian functionaries partly depends on the incomes from mining permits. Also, the ‘progressive’ go more and more over to large scale livestock breeding and thus need more land than before. Jerry Kammer, a journalist who went there to make an enquiry, concluded in 1980: ‘The family who gets the most profit from this way of doing business is the Sekaquaptewa family. The Sekaquaptewas are the richest Hopis and own the biggest livestock herd. Mormons. Wayne Sekaquaptewa also owns the Hopi daily paper and used to be president of the Mormon church of the reservation. His brother Abbot is the present chairman of the Hopi council.’

The campaign leader is John Boyden, however. With the help of Peabody Coal Company, a group of bankers from Utah and WEST, an association of interested energy companies, he is constantly busy in Washington D.C. attempting to win Congress to his case. The Congress gets to hear that the Navajos have broken into Hopi land and refuse to leave. A complete war on the ground would be going on. Meanwhile a Public Relations firm hired by the Hopi council, Evans & Associates from Salt Lake City, is staging that ground war. They circulate photos of burned camps and destroyed barns, which are eagerly taken over by most newspapers. The Washington Post wrote on July 21st 1974: ‘Evans & Associates also represent 23 service companies who had been installing power plants and strip mines in the Four Corners area… Those companies told their customers that the Hopis were “good Indians” who would not stop the thing on which their air conditioning functioned.’

The campaign is successful. In 1974 a Congress distracted by Watergate adopts Public Law 93-531, zealously advocated by senator of Arizona Barry Goldwater, among others. According to this law the Joint Use Area must be divided by a six hundred kilometer long barbed wire fence into a Navajo and a Hopi parts; the ten thousand Navajos living on the wrong side of the fence must kill or sell ninety percent of their livestock in preparation of their deportation; moreover there is a ban on building, improving or repairing houses and barns. A relocation commission will organize the deportation of the Navajos. They get a ‘compensation’ of five thousand dollars if they ‘voluntarily’ leave within five years. Apart from that the law promises to ‘minimize the negative impact’ by giving them land elsewhere. The government will provide ‘decent hygienic housing’ and the infrastructure for the community: schools, hospitals, roads, etc. Because in the reservation there is no more room. The land is already overgrazed and it is difficult to survive on it.

A narrow twenty percent of the inhabitants of the JUA have in between been relocated, often under pressure. This started to reveal the extent of the tragedy implied by PL 93-531.

DEPRESSIONS AND SUICIDES

The relocated Navajos ended in individual family housing, in lower middle class racist suburban towns. The small houses had wall plugs and gas and water pipes, but electricity, gas and light were not always available. To say nothing of the Promised Land. Forty percent of the relocated Navajos do not understand English and the majority of them had never been wage workers or paid taxes. But it is difficult now, in their small gardens, to remain independent sheep breeders. They must try to survive in a completely alien economic and bureaucratic system, while they have little chance to find a job, considering their background. Most of them soon get into troubles as they must pay taxes or suddenly get bills for gas, electricity and medical costs. Credit companies rushed to cleverly exploit there lack of experience with economic matters. For instance they convinced them to give their houses as security for loans which credit companies knew they would never be able to pay back. Other houses were sold for a quarter of their value. In between, fifty percent of the Navajos relocated in Flagstaff have lost their house. Remarkably enough, the relocation commission keeps buying those houses two or three times again, apparently without wondering what happened to the previous owners.

Most government promises about schools and health services turned out to be void. But for the Dineh much worse than their material situation was the separation from their land. With their land, to which their religion and their existence are tightly bound, the ground also metaphorically disappeared from under their feet. They see their culture being destroyed, their community life being split: ‘This seems to be the end of us’ says a relocated woman. ‘Our plans for the future of the children have fallen apart. We feel very lonely since the relocation. It looks like a prison here. We wonder why we did it. If we had not accepted to be relocated, maybe our daughter would not have died.’ It is a fact that many, apart from depression and alcoholism, suffer from health problems. The mortality is high. Under the emotional stress families fall apart and the number of suicides has greatly increased.

Some relocated Navajos returned illegally to their previous land. But it is more and more difficult to survive there. Due to the ban on building and repairing more and more growing families live in slowly deteriorating hogans, the traditional wooden cabins. If they try to do anything to improve their housing, they see the result of their efforts being destroyed under their very eyes by government workers. With only ten percent of the livestock they used to have they can hardly stay alive: their food consists of bread, coffee and potatoes. But they are determined not to be chased away. It has been announced in Reagan’s name that the army would be called in. The old Navajo women are prepared for it. ‘We have faced soldiers before. Until now we survived it.’ The task won’t be easy for the militaries. Some women have already been arrested for shooting over the heads of fence builders, but nobody has been charged until now. And the fence won’t keep standing.

Some relocated Navajos returned illegally to their previous land. But it is more and more difficult to survive there. Due to the ban on building and repairing more and more growing families live in slowly deteriorating hogans, the traditional wooden cabins. If they try to do anything to improve their housing, they see the result of their efforts being destroyed under their very eyes by government workers. With only ten percent of the livestock they used to have they can hardly stay alive: their food consists of bread, coffee and potatoes. But they are determined not to be chased away. It has been announced in Reagan’s name that the army would be called in. The old Navajo women are prepared for it. ‘We have faced soldiers before. Until now we survived it.’ The task won’t be easy for the militaries. Some women have already been arrested for shooting over the heads of fence builders, but nobody has been charged until now. And the fence won’t keep standing.

GENOCIDE

Resistance grows among traditional Navajos. They also more and more clearly attack the present chairman of the council, Peterson Zah. Zah presents himself as representative of the traditional people but does not work against the administration. He negotiates on how the deportations must be carried out, he does not stand against them. Together with General Electric and Bechtel, he even made plans to install a power plant of twenty thousand megawatt and a strip mine on Navajo land. The ‘old’ Navajos have nothing to expect from him. It is mainly the traditional Hopis who support them in their resistance to governmental plans. The ordinary Hopis have as little to win as the Dineh from their council’s plans, which do not leave any doubts about the fact that they will use the newly gained land for coal strip mining, of which mainly council members will get profit. Despite all the external attempts to set them against each other, most Hopis remain on the same line as the traditional Navajos. In 1981 Thomas Banyacaya published in their name a declaration of solidarity with the Dineh.

In 1982 the Big Mountain-JUA Legal Defense/Offense Committee (BMLDOC) was created in Flagstaff. Under the leadership of Big Mountain elders, the BMLDOC gives free juridical assistance to the Indian struck by the relocation program. It takes a number of legal actions against the state and campaigns to repeal PL 93-531.

Some support has come from an unexpected side. On January 1st 1982 the director of the relocation commission, Leon Berger, resigns. He calls the relocation program ‘an unprecedented disaster’ and announces that he will devote himself to the repealing of the law. In May of that year commission member Roger Lewis resigns on the same grounds.

International resistance to the consequences of PL 93-531 starts too. The jury of the Fourth Russell Tribunal, held in Rotterdam in 1980, concludes that according to the United Nations Convention it is a case of genocide. In the Netherlands NANAI, among others gets involved against the planned deportations and overall in Europe action and support groups arise.

AMENDMENTS

Even in the American Congress, expressions of concern can now be heard. Those apply mainly to the financial side of the program. The forty million dollars which PL 93-531 was going to cost have now increased to five hundred millions, en the total expenses could very well reach the two billions. In a time when drastic budget reductions are applied, the Congress cannot, towards the tax payers, allow itself to spend such an amount for an ‘intervention in a conflict between a bunch of Indian tribes’ (the image that still lives, thanks to the media). And it certainly cannot happen at all if the program, in the words of Congress member Les AuCoin, ‘can be called a major fiasco.’ A number of Congressmen begin to realize that the result of their intervention has been to turn a proud, economically independent people into a group of wretched homeless human beings depending on public help to survive. So have a few amendments been submitted aiming at postponing the forced deportations which, since July 7th of this year can happen at any time, for instance until sufficient housing has been built for the deported Navajos, which has been much delayed by the budget cuts policy. Nobody talks any more about the provisions concerning medical and educational services.

Of course, postponement does not make any difference. The deportation must not happen at all. As the Navajo resistant woman Roberta Blackgoat puts it ‘It is another way: a way of starvation and genocide’. The Dineh have as much right to their land, life and culture as the traditional Hopis. And the world needs them, because Big Mountain is everywhere .The economic, social and political forces that those people fight are also at work in the rest of the world. In a time in which the earth is getting destroyed by them, the Dineh are one of the last peoples knowing how to live without disturbing the balance of nature and having kept their spiritual unity with the earth. Let it remain like that. All support is necessary in the struggle against deportation.

Jansen