AKIMEL O’ODHAM: CONSTRUCTION OF LOOP 202 IS STILL CONTINUING AND ENCROACHING ON US

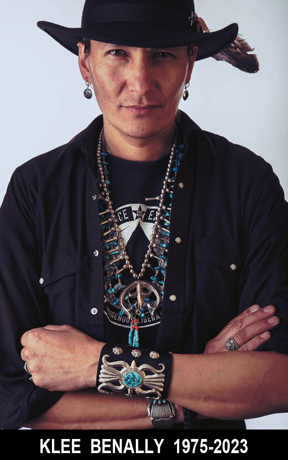

Andrew Pedro, Akimel O’odham

October 2, 2017

Interview and article by Christine Prat Français

The Loop 202 is a freeway leading around Phoenix, Arizona. It is partly existing east of the city and is now being extended westward. The decision to include the South Mountain Freeway in Loop 202 was taken in 1986. The final approval to extend it was received on March 10, 2015. The construction is planned to be completed in 2019. The extension implies destruction of a huge part of Moadag Do’ag, or South Mountain, which is sacred for the Akimel O’odham. A lot of destruction has already happened, but it is rapidly going on.

The Loop 202 is a freeway leading around Phoenix, Arizona. It is partly existing east of the city and is now being extended westward. The decision to include the South Mountain Freeway in Loop 202 was taken in 1986. The final approval to extend it was received on March 10, 2015. The construction is planned to be completed in 2019. The extension implies destruction of a huge part of Moadag Do’ag, or South Mountain, which is sacred for the Akimel O’odham. A lot of destruction has already happened, but it is rapidly going on.

The Loop 202 is also part of the “Sun Corridor”, a ‘recreation’ project, meant to develop a megacity from Phoenix to Tucson, maybe even from Prescott to Nogales.

As a matter of fact, Loop 202 extension is part of a much bigger project, the CANAMEX* project. It is a road project devised as part of NAFTA, a free trade agreement between the USA, Canada and Mexico, designed in 1993 and signed by Bill Clinton in 1994.

In September 2015, I had talked with Andrew Pedro, Akimel O’odham activist, about the consequences of the project for the Tribe, and their struggle against it. At the beginning of October 2017, we met again, to talk about the present situation, regarding the construction and the struggle against it.

In September 2015, I had talked with Andrew Pedro, Akimel O’odham activist, about the consequences of the project for the Tribe, and their struggle against it. At the beginning of October 2017, we met again, to talk about the present situation, regarding the construction and the struggle against it.

“It’s the fall of 2017, and the construction of the 202 is still continuing” said Andrew. He went on talking about the legal aspect of the issue, as a court case against construction is now in the Court of Appeal of the 9th Circuit in San Francisco. Arguments were supposed to be heard on October 28th. Andrew Pedro wrote then “People from the Tribal Council went and attended the oral arguments. Now it’s in a state of limbo again. The Court could take as long as six months to make a ruling in the case. The other litigants, PARC, said this is probably the end for them. They don’t believe that the Supreme Court will take the case”. It is not sure that the ruling will give more hope of stopping the construction, as the 9th Circuit three judges already denied injunctions to stop construction. Andrew Pedro pointed out that, the project being in a Court case, construction should be held. However, ADOT has just stepped up construction speed, very likely hoping that when the Court will make a ruling, it will be too late to have a substantial effect on the project.

At the beginning of October, construction was mainly happening in what they call the Pecos segment, in the town of Ahwatukee, along the Pecos road. Many people in Ahwatukee, which is in ‘white’ territory, but where some O’odham live, are also against the Freeway.

At the beginning of October, construction was mainly happening in what they call the Pecos segment, in the town of Ahwatukee, along the Pecos road. Many people in Ahwatukee, which is in ‘white’ territory, but where some O’odham live, are also against the Freeway.

The activists struggling against the project never expected much from the Court system, knowing that courts are not on their side. “… on one hand, they would protect Arizona’s children and resources, which is predominantly a White group of people based out of Ahwatukee, and then you have the Gila River Indian Community with all their own legislation, but the lawsuits are joined, so that, if one case loses, the other case loses. So, we’re kind of in a big mess with that as well.” They don’t trust their Tribal Council either, who “are not really fulfilling their purpose of protecting the community and protecting our sacred places and protecting our inherent right to be at these places”.

There are other areas under construction. Among others, the Salt River segment, on the west side of the mountain, where bridge construction was about to start, pillars and concrete having been already brought. There is also construction on Interstate 10, 79th Avenue, to 43rd Avenue, in between, a major freeway interchange is being built.

“For us, as O’odham people, it is hard to really put a focus on which areas need to be handled properly and first. Because that freeway is one big project and is 22 miles long, and with all those constructions happening, it’s hard to say what could really stop them in one area, as they’ll continue in another area” Andrew stated. “Nonetheless, those of us who do this work have not lost hope that we can still save our mountain from being destroyed, from further destruction.”

A lot of people are demoralized and feel defeated, but, says Andrew, “we just got to keep moving forward.”

Although outsiders mainly see the actions and protests, and thus view the issue as mainly political, O’odham people, and other Indigenous peoples, see another side to it, the cultural side, meaning “who we are.” …”that is more powerful than the political world, because that keeps us grounded, it keeps us back to our roots and where we really come from, and why these things are important to us and why these places and these mountains are important to us in the first place.”

Then Andrew explains that there are some new people coming in to help, Indigenous people who understand the cultural side. And also, “because now, there are more people from all over taking interest in the struggle itself because it’s gonna later on affect other areas too. Be it in Tohono O’odham Nation, even in Salt River, already affected by the 101 freeway, because that crosses their area. So, they know how we’re feeling out here. It’s the same thing because we are O’odham people, Salt River is O’odham people…”

The effects of the ‘greater’ projects, the Sun Corridor and the CANAMEX, are also felt by Indigenous people outside the Gila River Indian Community. The CANAMEX project is a super highway from Guaymas, in Mexico, to Edmonton, in Alberta, Canada. Road construction and repair has already started, in Tucson, Nogales, Phoenix and in Casa Grande. In Casa Grande, a ‘free trade zone’, an international trade hub, called Phoenix Mart, is supposed to open next year.  “So, it will just keep them encroaching and encroaching on us. We are still stuck in the middle of where so-called progress is supposed to be made, and development is supposed to come from” Andrew stated. Of course, tribal politics go with it, as they only see the money that could be made. However, it is less than certain that development brings any progress to the people, as the example of Interstate 10 shows: when it was built through the Gila River, they were promised roads, housing, jobs…

“So, it will just keep them encroaching and encroaching on us. We are still stuck in the middle of where so-called progress is supposed to be made, and development is supposed to come from” Andrew stated. Of course, tribal politics go with it, as they only see the money that could be made. However, it is less than certain that development brings any progress to the people, as the example of Interstate 10 shows: when it was built through the Gila River, they were promised roads, housing, jobs…  but none of it happened, “if you drive through the I10 now, it’s completely bare.” With the new developments – Phoenix Mart, development in Tucson – “…these cities are coming closer to us, and that’s the example of what’s going to happen to us in the long run, we’ll possibly get run over. …With the 202, people who drive over the Pecos Road right now, looking one way, they see Ahwatukee, looking the other way, they see the Reservation.”

but none of it happened, “if you drive through the I10 now, it’s completely bare.” With the new developments – Phoenix Mart, development in Tucson – “…these cities are coming closer to us, and that’s the example of what’s going to happen to us in the long run, we’ll possibly get run over. …With the 202, people who drive over the Pecos Road right now, looking one way, they see Ahwatukee, looking the other way, they see the Reservation.”

However, the important part is the mountain. It is in the center, it is the central segment of the freeway.  There is also a housing development, a subdivision of Ahwatukee, between the ridges of Moadag Do’ag. The project is independent from the freeway, it is not ADOT, but possibly in the way. The mountain has already been blasted for a road. “That construction is also not finished, but it’s there, the land has been wiped and destroyed in the middle of those ridges, and we’re left with a mountain that has already been desecrated enough. And it’s not even half of what ADOT wants to do” says Andrew.

There is also a housing development, a subdivision of Ahwatukee, between the ridges of Moadag Do’ag. The project is independent from the freeway, it is not ADOT, but possibly in the way. The mountain has already been blasted for a road. “That construction is also not finished, but it’s there, the land has been wiped and destroyed in the middle of those ridges, and we’re left with a mountain that has already been desecrated enough. And it’s not even half of what ADOT wants to do” says Andrew.

The present road is a two lanes road, the freeway is supposed to be four lanes on each side, “which is a massive cut in the mountain”.

What has already been done is bad enough, but “there is still another fight coming, the war isn’t over,” adds Andrew Pedro, “because the scale of the project is much larger”. The project is in fact the CANAMEX Corridor, which will encroach on many other Indigenous areas, down to Mexico: the O’odham territory is cut by the border. Tohono O’odham and Hia C-ed O’odham territory goes across the border. Villages on the other side will be affected too.

Andrew Pedro states “We are being attacked here, we are in the center of Arizona, the O’odham people are here being attacked by the 202, the Tohono O’odham Nation is being attacked with the border, and then, in the North, there are plenty of struggles, from uranium mines to Snowbowl. Arizona is pretty much known for its attacks against Indigenous People.”

The reason for these attacks has a name: Capitalism. “That’s what kind of connect it all. Because the development that is happening is to help facilitate trade. That is Capitalism in Arizona, if you really want to get down to the root of what is happening to us. It’s always gonna be the money that is the driving force behind a lot of these projects.” The 202 is a trade corridor, so is the Sun Corridor. Those projects are supposed to bring business and development to the region, but it hardly has any effect on the local economy. “It doesn’t help anybody at all. But by doing so, they bypass Indigenous People. They don’t think about what’s going to happen to our ceremonial grounds and our sacred places.”

In the Gila River Indian Community, ADOT illegally uses Reservation roads. As a non-tribal entity, they should have a permit to use those roads, specially as the freeway is just off the Reservation. But they use those roads because it is a little quicker to reach the construction sites.

Construction has drastically restricted O’odham people’s accessibility to the sacred mountain. It has disturbed ancestors remains, human remains have been excavated and are still withheld by the state of Arizona. People fear the increased pollution which will affect their health.

Andrew Pedro concludes “We will continue to fight, as they have to know they’re going to pay for this, somehow. We will do everything we can. Whether that means protests and direct actions… It is a risk and people do need to realize what this mountain means to us and why these risks are important.”

Depuis plusieurs années, des membres de la communauté Autochtone de Gila River, et plus particulièrement le Collectif de Jeunesse Akimel O’odham [Akimel O’odham Youth Collective – AOYC], s’opposent au projet d’extension du périphérique 202 à travers leur Réserve, et à travers Moadak Do’ag, la Montagne du Sud, sacrée pour les O’odham. Le projet détruirait la Montagne du Sud sur une largeur d’autoroute à 8 voies, et par endroits sur une hauteur équivalent à deux étages. Des terres seraient détruites, ainsi que des maisons, et des habitants devraient déménager. De plus, la pollution – et les maladies pulmonaires qu’elle provoque – augmenterait considérablement, la drogue et les armes à feu entreraient encore plus facilement dans la région et les Réserves.

Depuis plusieurs années, des membres de la communauté Autochtone de Gila River, et plus particulièrement le Collectif de Jeunesse Akimel O’odham [Akimel O’odham Youth Collective – AOYC], s’opposent au projet d’extension du périphérique 202 à travers leur Réserve, et à travers Moadak Do’ag, la Montagne du Sud, sacrée pour les O’odham. Le projet détruirait la Montagne du Sud sur une largeur d’autoroute à 8 voies, et par endroits sur une hauteur équivalent à deux étages. Des terres seraient détruites, ainsi que des maisons, et des habitants devraient déménager. De plus, la pollution – et les maladies pulmonaires qu’elle provoque – augmenterait considérablement, la drogue et les armes à feu entreraient encore plus facilement dans la région et les Réserves.

C’est ce dont parle Andrew Pedro, membre du Collectif de Jeunesse Akimel O’odham dans la vidéo ci-dessous, enregistrée le 28 septembre 2015.

LE PERIPHERIQUE 202 FAIT PARTIE D’UN PROJET INFINIMENT PLUS VASTE

Par Christine Prat

In English

Le projet d’extension du périphérique 202 – une bretelle qui contourne Phoenix par l’est pour l’instant – à travers le territoire Akimel O’odham de Gila River, s’inscrit dans un projet beaucoup plus vaste. Il est question de créer un axe de transports commerciaux allant du port de Guaymas, au Mexique, jusqu’en Alberta, au Canada, dans la région où sont extraits les désastreux sables bitumineux. L’axe doit aussi passer à proximité des sables bitumineux d’Utah et de gisements de gaz de schistes. Cet axe emprunte des autoroutes existantes, mais de nouvelles portions doivent être construites là où les routes existantes ne permettent pas une circulation intense de poids lourds. Entre autres, une prolongation de la bretelle 202 vers l’ouest de Phoenix, à travers la Montagne du Sud, sacrée pour les Autochtones, et la construction d’une nouvelle autoroute entre Phoenix et Las Vegas, la route actuelle n’étant pas adaptée au trafic prévu. Le projet comprend aussi la construction de ‘ports intérieurs’ avec des ‘zones de commerce extérieur’ qui permettraient un allègement des taxes pour les entreprises privées.

Le projet d’extension du périphérique 202 – une bretelle qui contourne Phoenix par l’est pour l’instant – à travers le territoire Akimel O’odham de Gila River, s’inscrit dans un projet beaucoup plus vaste. Il est question de créer un axe de transports commerciaux allant du port de Guaymas, au Mexique, jusqu’en Alberta, au Canada, dans la région où sont extraits les désastreux sables bitumineux. L’axe doit aussi passer à proximité des sables bitumineux d’Utah et de gisements de gaz de schistes. Cet axe emprunte des autoroutes existantes, mais de nouvelles portions doivent être construites là où les routes existantes ne permettent pas une circulation intense de poids lourds. Entre autres, une prolongation de la bretelle 202 vers l’ouest de Phoenix, à travers la Montagne du Sud, sacrée pour les Autochtones, et la construction d’une nouvelle autoroute entre Phoenix et Las Vegas, la route actuelle n’étant pas adaptée au trafic prévu. Le projet comprend aussi la construction de ‘ports intérieurs’ avec des ‘zones de commerce extérieur’ qui permettraient un allègement des taxes pour les entreprises privées.

L’ALENA (NAFTA) ET LE CANAMEX

En fait, ces projets autoroutiers ont été pensés dans le cadre de l’ALENA [NAFTA en anglais], un accord de libre échange de 1993 entre les Etats-Unis, le Canada et le Mexique, signé par Bill Clinton en 1994. L’axe autoroutier (et dans le futur ferroviaire, portuaire, incluant peut-être des pipelines, etc.) baptisé CANAMEX, a été conçu dès la mise au point de l’accord. Entretemps, et vu que des protestations s’élèvent, les promoteurs du projet prétendent que le CANAMEX a pour but de désengorger les ports de la côte ouest des Etats-Unis en faisant passer une partie des marchandises échangées avec les pays du Pacifique par le port de Guaymas, au Mexique, dont la capacité devrait être doublée. Cependant, il est évident que le fait que les dockers mexicains sont beaucoup moins payés, ont beaucoup moins de protections sociales et des règles de sécurité beaucoup moins strictes que les dockers syndiqués des Etats-Unis, et que c’est donc beaucoup moins cher pour les entreprises de passer par Guaymas, pèse de tout son poids dans le projet. Plus généralement, lorsque l’ALENA a été conçu, ses promoteurs affirmaient que çà créerait des emplois dans les trois pays. Evidemment, il n’en est rien. De nombreux emplois ont été délocalisés, des usines se sont installées à la frontière, côté mexicain, pour employer des immigrants refoulés, qui n’ont même pas assez d’argent pour retourner dans les régions d’où ils viennent, qui doivent travailler pour presque rien et sans aucune garantie – ils travaillent quand ça arrange l’entreprise et ne sont pas payés quand on n’a pas besoin d’eux (voir l’article d’Anne Vigna dans ‘Manière de Voir’ 128, avril-mai 2013).

Depuis, l’ALENA (NAFTA) doit être prolongé par le TTP – TransPacific Partnership [Partenariat Trans Pacifique, jusqu’à maintenant, 12 pays sont arrivés à un accord : L’Australie, Brunei, le Canada, le Chili, le Japon, la Malaisie, le Mexique, la Nouvelle Zélande, le Pérou, Singapore, les Etats-Unis, et le Vietnam] – et par le TAFTA à travers l’Atlantique.

A part le CANAMEX, le Canada veut aussi construire des pipelines allant d’Alberta à la côte du Pacifique pour transporter ses sables bitumineux à travers le territoire des Autochtones Unist’ot’en et le territoire Wet’suwet’en, qui n’a jamais été cédé légalement, et dont les habitants continuent à résister. Il y a également de la résistance au Mexique contre La Parota Dam et la privatisation.

PARTENARIAT PRIVE PUBLIC

Les pouvoirs publiques des trois pays concernés, (fédéraux, des états et des municipalités) n’ont jamais eu les moyens de financer le projet CANAMEX et ont donc conclu des ‘Partenariats Privé-Public’ ou P3, qui pratiquement en reviennent à une quasi privatisation du projet et des terres confisquées : les entreprises privées avancent l’argent, mais les autorités doivent bien sûr rembourser et de plus garantir des bénéfices aux investisseurs. Dans le cas du CANAMEX, il a même été envisagé de faire des autoroutes à péage, ce qui jusqu’à maintenant n’existe pas aux Etats-Unis. [Pensez au Partenarial Privé-Public entre les pouvoirs publics français et Vinci !]

LA FRONTIERE

Si l’ALENA devait imposer la liberté totale de circulation des marchandises, il n’en est pas de même pour les humains. L’accord a donc été accompagné d’une politique délirante contre l’immigration, la militarisation des zones frontalières, la construction d’un mur par endroits, d’une barrière ailleurs, l’instauration de visas (au prix inabordable) pour les Autochtones dont le territoire a été divisé par les conquêtes des Etats-Unis sur le Mexique officialisées par le Traité de Guadalupe Hidalgo en 1848, de caméras de surveillance pas toujours dirigées vers le Mexique, de drones, de flics de la patrouille des frontières qui arrêtent qui bon leur semble, roulent à tombeau ouvert sur les pistes des réserves au prix de nombreuses vies de piétons, etc. La création de ‘ports intérieurs’ avec des ‘zones de commerce extérieur’ impliquerait la présence d’agents de la Protection des Douanes et des Frontières, ce qui accroitrait considérablement l’insécurité des immigrés bien au-delà des régions frontalières.

Si l’ALENA devait imposer la liberté totale de circulation des marchandises, il n’en est pas de même pour les humains. L’accord a donc été accompagné d’une politique délirante contre l’immigration, la militarisation des zones frontalières, la construction d’un mur par endroits, d’une barrière ailleurs, l’instauration de visas (au prix inabordable) pour les Autochtones dont le territoire a été divisé par les conquêtes des Etats-Unis sur le Mexique officialisées par le Traité de Guadalupe Hidalgo en 1848, de caméras de surveillance pas toujours dirigées vers le Mexique, de drones, de flics de la patrouille des frontières qui arrêtent qui bon leur semble, roulent à tombeau ouvert sur les pistes des réserves au prix de nombreuses vies de piétons, etc. La création de ‘ports intérieurs’ avec des ‘zones de commerce extérieur’ impliquerait la présence d’agents de la Protection des Douanes et des Frontières, ce qui accroitrait considérablement l’insécurité des immigrés bien au-delà des régions frontalières.

LE ‘CORRIDOR DU SOLEIL’

Outre l’axe CANAMEX, le périphérique 202 doit aussi faire partie d’un projet appelé ‘Corridor du Soleil’, qui a pour but de créer une mégalopole allant de Phoenix à Tucson, et peut-être même de Prescott à Nogales. Phoenix a déjà plus de 6 millions d’habitants, Tucson a des rues de 40 km ou plus. Ces villes consomment une quantité d’énergie et d’eau bien au-dessus de la capacité de cette région désertique. Les rivières, les nappes souterraines – surtout celles des Réserves Autochtones – sont pillées et s’épuisent. Dans la Réserve dite de Gila River, la Gila est à sec, ainsi que la Salt River au niveau de Phoenix. Pendant des années, les résidents de Gila River ont été privés d’eau et ont dû renoncer à une bonne part de leur agriculture, avec pour résultat des taux d’obésité et de diabète exceptionnels (les produits de l’agriculture traditionnelle étant remplacés par des supermarchés). Plus récemment, les autorités leur ont fourni beaucoup d’eau, mais il est trop tard pour rétablir les cultures traditionnelles, des terres sont réquisitionnées pour le projet d’autoroute et il est probable que l’eau soit objet de commerce. La pollution due au trafic routier cause déjà de nombreuses maladies pulmonaires, ce sera décuplé si le périphérique 202 est prolongé à travers la réserve. Et, une fois de plus, des sites sacrés pour les Autochtones seront détruits.

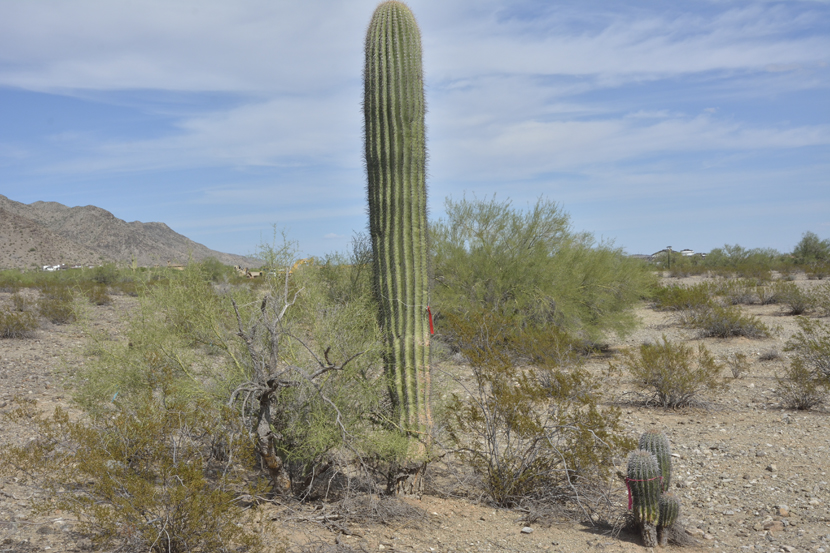

La Montagne du Sud: les cordelettes jaunes indiquent ce qui doit être détruit

Les rubans rouges indiquent les cactus qui doivent être supprimés

Sources (en anglais):

Interview de Kevin et Andrew, Akimel O’odham (voir vidéo)

Akimel O’odham Youth Collective

Stop CANAMEX