Text Leona Morgan and Christine Prat En français

February 16, 2020

Also published on Censored News

Leona Morgan, a Diné [Navajo] antinuclear activist, was invited by the CSIA-Nitassinan on February 16th, 2020. She talked about her work, nuclear colonialism, historical and present impacts of uranium on the people of her community, actions that have been undertaken and actions to be undertaken in order to resist.

Leona Morgan, a Diné [Navajo] antinuclear activist, was invited by the CSIA-Nitassinan on February 16th, 2020. She talked about her work, nuclear colonialism, historical and present impacts of uranium on the people of her community, actions that have been undertaken and actions to be undertaken in order to resist.

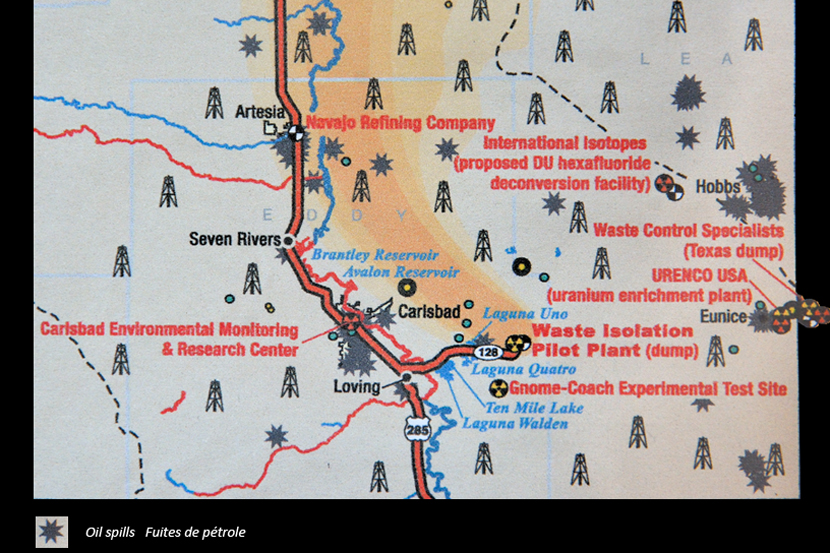

You can find on this site more information on Leona’s work and on her visit in 2019 to Bure, France, where a waste burial site is being dug. (A waste burial site is also planned in New Mexico, where she lives). The Navajo Nation [“reservation”] and the surroundings, have been particularly impacted by uranium mines and other nuclear industries.

[Click on maps and photos to see them in larger, readable format]

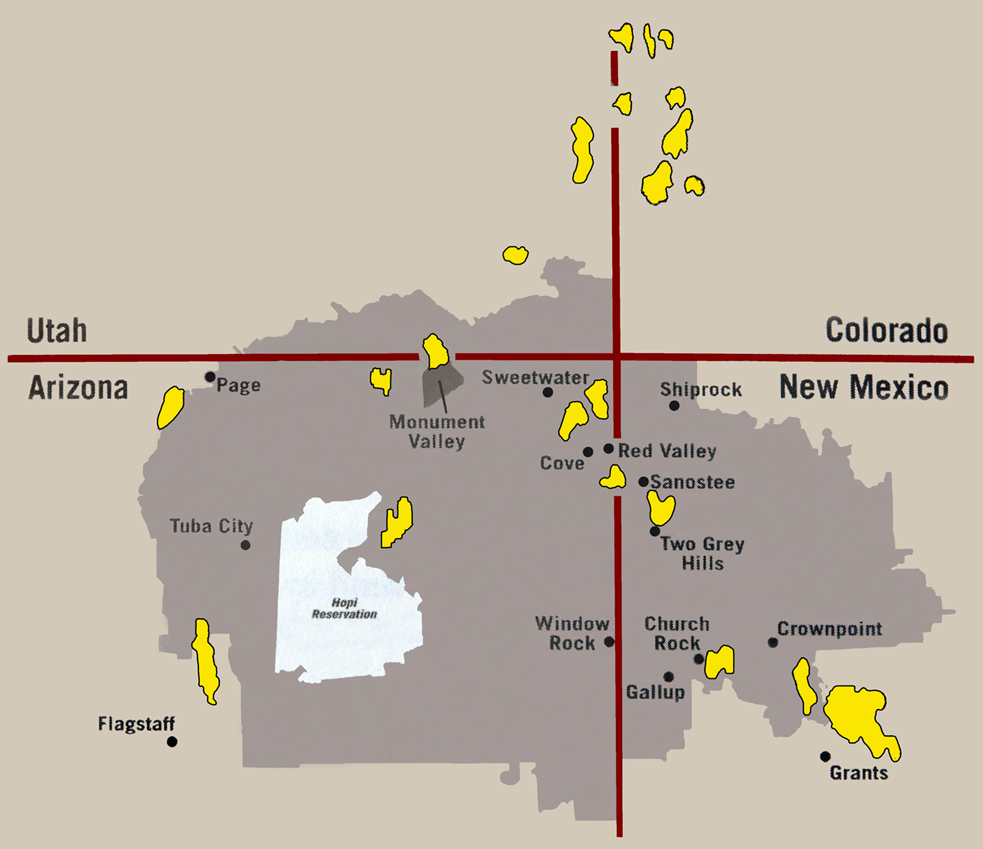

Leona started her presentation by showing a picture of Monument Valley, a world-famous image, as many movies, especially ‘Western’ movies, were made there. This is also where uranium was first mined in the Navajo Nation, in the 1940’s. Mining developed continuously during the Cold War time.

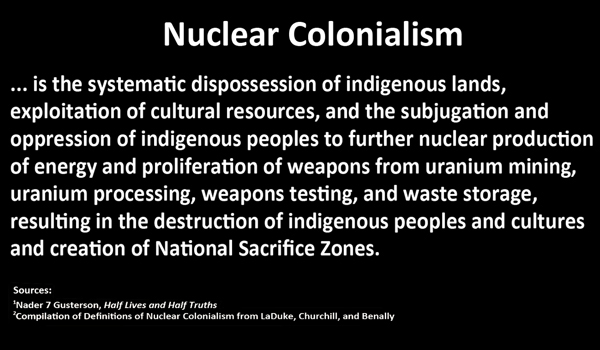

She then gave a definition of nuclear colonialism, a term first created by Winona La Duke. Leona explained “Quite simply, nuclear colonialism can be explained as a systematic way by which the governments have exploited and destroyed Indigenous Peoples lands, for use of uranium to make nuclear weapons, as well as today, nuclear energy. This is a form of institutionalized racism, and also environmental racism. It is also nuclear colonialism which caused a lot of contamination and impacts to people by weapons testing.”

She then gave a definition of nuclear colonialism, a term first created by Winona La Duke. Leona explained “Quite simply, nuclear colonialism can be explained as a systematic way by which the governments have exploited and destroyed Indigenous Peoples lands, for use of uranium to make nuclear weapons, as well as today, nuclear energy. This is a form of institutionalized racism, and also environmental racism. It is also nuclear colonialism which caused a lot of contamination and impacts to people by weapons testing.”

She further stated that “In the whole world, uranium mining happens mostly on Indigenous Peoples lands. We do not have an exact number but we estimate that 70% of uranium mining happen on Indigenous lands. Many of the weapons tests were also done on Indigenous Peoples lands.” [France tested their atomic bombs in Tuareg territory in Algeria, until 1967, then in Mururoa, in ‘French’ Polynesia. Then, the national uranium company – which has changed names several times – destroyed the Tuareg territory in Northern Niger].

She also pointed out that most weapons testing occurred in Western Shoshone territory, in Nevada. When media mention it, they always call the region the ‘Nevada Desert’, neglecting to mention the fact that it is still the territory of Indigenous communities, mainly Western Shoshone, but there is also a Paiute reservation nearby the testing area. Leona: “There were over 900 tests done in that area,” “and I want to say that a friend of mine, Ian Zabarte, explains that, as Indigenous people, they cannot go back to their homeland, because of the contamination.” [In the early 1960’s, they also tested bombs on the Island Bikini, which is still unhabitable today. Strange enough, the name became fashionable for sexy bath suits and a silly popular song].

She also pointed out that most weapons testing occurred in Western Shoshone territory, in Nevada. When media mention it, they always call the region the ‘Nevada Desert’, neglecting to mention the fact that it is still the territory of Indigenous communities, mainly Western Shoshone, but there is also a Paiute reservation nearby the testing area. Leona: “There were over 900 tests done in that area,” “and I want to say that a friend of mine, Ian Zabarte, explains that, as Indigenous people, they cannot go back to their homeland, because of the contamination.” [In the early 1960’s, they also tested bombs on the Island Bikini, which is still unhabitable today. Strange enough, the name became fashionable for sexy bath suits and a silly popular song].

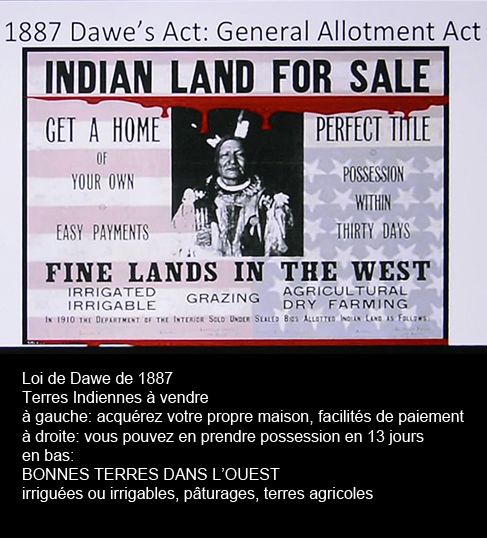

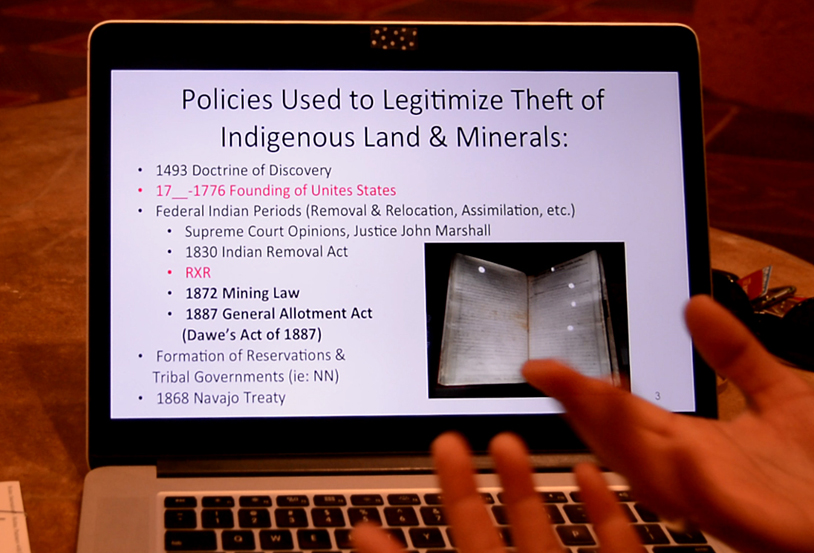

Talking about the history of nuclear colonialism, she said “I shall start from the beginning of the systematic way that racism and genocide have become a law. There is a document that was created in 1493, called ‘The Doctrine of Discovery’. I am wondering how many of you know of that document? Most of the time maybe one or two people raise their hands, there are more than one or two here, so that’s great!” She further explained that the document – as a matter of fact a ‘Papal Bull’ – was created in Europe, in order to give the Church blessings to colonialism: “this was a document that was created here in Europe, that basically started to open ways to colonization of lands in different parts of the world. And then this is what allowed the various countries to take lands, to take people, to enslave people and to kill people. The idea was that Indigenous people are not really human, that we are less than human, so therefore it is okay to take our land and commit genocide in the name of, at the time, Christendom or to promote the Church. It’s okay because we don’t have rights as others, we are not humans, it’s the idea. So, moving forward in the United States, this was also used as the foundational papers for the United States and other countries.”

She then described the different periods of the policy of European settlers towards Native Americans: “At the beginning – the founding of the United States – they created what is called the federal Indian periods. So, in the United States, at the beginning, the first Indian period was Removal. So, when the western settlers came in, they wanted to move on the land. In order to clear the land, that meant clear the land of the people, which is legalized genocide. And also, Relocation, which was pushing the Indigenous Peoples westward. Later, they moved to what was called Assimilation, where they took young Indigenous children to western schools, where they were forced to speak English and change their way of life.” As well in the United States as in Canada, children were kidnapped from their family and put in Indian Boarding schools, where they were very badly treated – close to torture – and many of them died. Recently, many Indigenous people in the United States and Canada started to talk about their parents’ stories in those school, and to make it to the media. [The same happened, and was still happening not so long ago, in French Guiana].

She then described the different periods of the policy of European settlers towards Native Americans: “At the beginning – the founding of the United States – they created what is called the federal Indian periods. So, in the United States, at the beginning, the first Indian period was Removal. So, when the western settlers came in, they wanted to move on the land. In order to clear the land, that meant clear the land of the people, which is legalized genocide. And also, Relocation, which was pushing the Indigenous Peoples westward. Later, they moved to what was called Assimilation, where they took young Indigenous children to western schools, where they were forced to speak English and change their way of life.” As well in the United States as in Canada, children were kidnapped from their family and put in Indian Boarding schools, where they were very badly treated – close to torture – and many of them died. Recently, many Indigenous people in the United States and Canada started to talk about their parents’ stories in those school, and to make it to the media. [The same happened, and was still happening not so long ago, in French Guiana].

Leona then named other tools that were used for colonization, such as railroads and mining, and the creation of ‘Tribal governments’: “there was also the creation of what we call ‘tribal governments’, which is a typical type of western government that was not natural to our people. These western governments often do not promote the will of the community people, most of the time they are puppets of the federal government.” She added “at the beginning, they were often puppets of the United States, but today there is a move toward decolonization. These western governments, in the beginning focused more on capitalism and things that were no part of our traditional ways of living. In the last 50 years, there has been a great change, for tribal governments, to create our own laws that are for the protection of our traditional ways, our sacred sites, our human rights, and it is getting stronger and stronger every day.”

Leona then named other tools that were used for colonization, such as railroads and mining, and the creation of ‘Tribal governments’: “there was also the creation of what we call ‘tribal governments’, which is a typical type of western government that was not natural to our people. These western governments often do not promote the will of the community people, most of the time they are puppets of the federal government.” She added “at the beginning, they were often puppets of the United States, but today there is a move toward decolonization. These western governments, in the beginning focused more on capitalism and things that were no part of our traditional ways of living. In the last 50 years, there has been a great change, for tribal governments, to create our own laws that are for the protection of our traditional ways, our sacred sites, our human rights, and it is getting stronger and stronger every day.”

For Europeans who believe that most Indigenous people are extinct, (‘killed by John Wayne’,) she stated “I just want to remind everybody that right now in the United States, there are hundreds of Indigenous Peoples. In North America – we call it Turtle Island – there are many, many, many Indigenous Nations that are still alive and speaking our own languages, and practicing our traditional ways today. Of course, there are also many Indigenous Peoples in South America and other parts of the world who are practicing their cultures until today. In the United States, there are 573 Nations that are recognized by the federal government.”

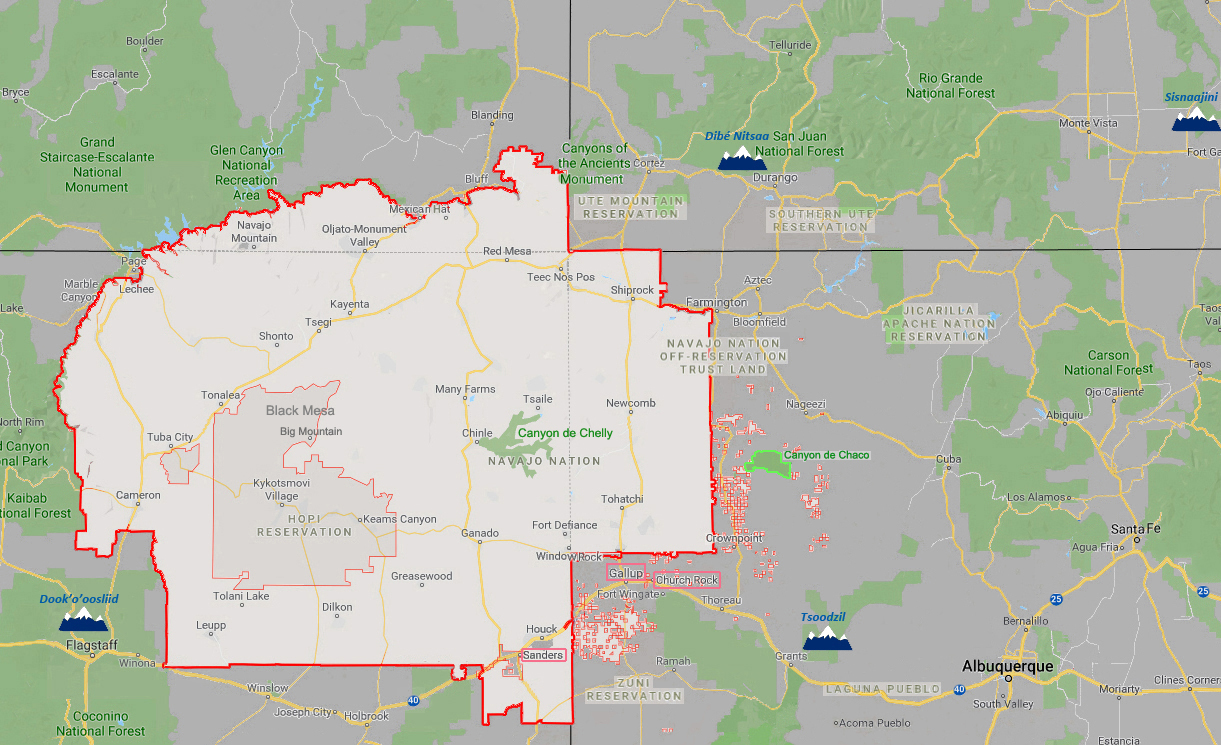

She then said that, in her presentation, she would focus on her own community, the Navajo Nation, but also talk about the neighbors around, tribes known as ‘Pueblos’, who are also impacted by uranium mining and nuclear activities.

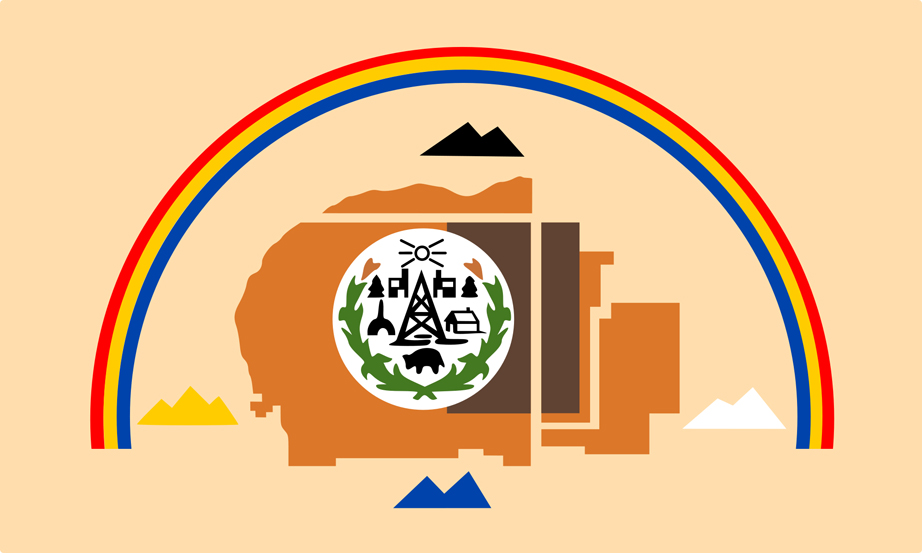

She first explained where her community lives, pointing out the difference between what is now called the Navajo Nation (originally the Reservation) and the traditional land of the Diné, between four sacred mountains.

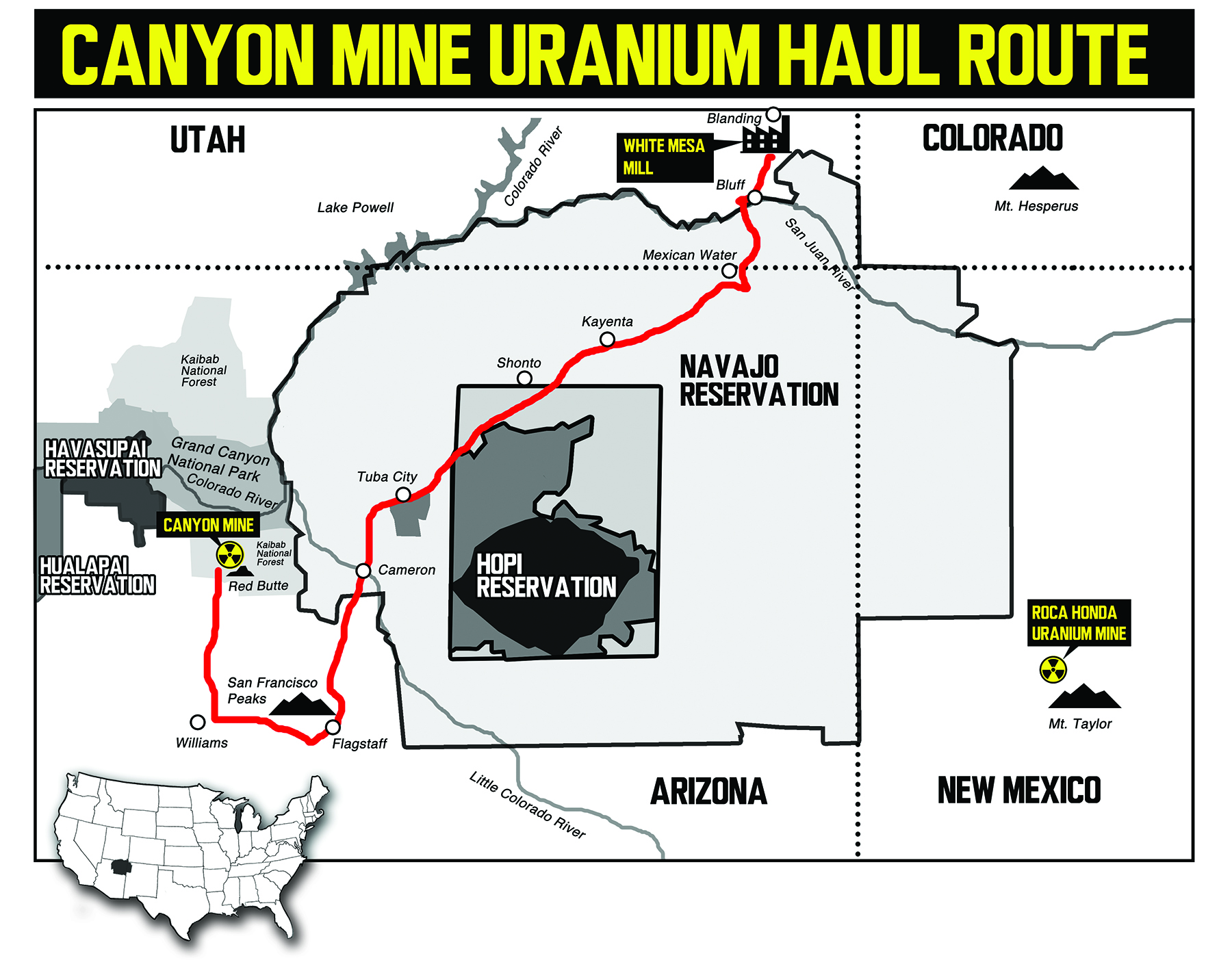

She then mentioned the transport issue – of uranium ore, contaminated water, waste – an issue that made local activists create the Haul NO! campaign, about which she told more later. A map was circulated among the audience:

She further went to “explain a little bit more, about the difference between the western government and the traditional people. It is a very important thing to understand that we call ourselves ‘Diné’, but our government is called ‘Navajo’. To be Diné and to live as a Diné, is to continue the way our ancestors lived. The community at home often is more concerned about protection of our Mother Earth, because this is our home, and if we damage our Mother, then we also will suffer. However, the Navajo Nation as a government was created by outside forces and was more concerned with economic development. This included resources extraction, as you can see on the flag, some oil drilling operation, and other forms of economic development.”

Although the focus of her talk was on uranium mining, she also mentioned other types of extraction impacting the Navajo Nation, mainly coal mines and coal fired power plants, as well as fracking for gas and oil. “There are many, many frontline communities that are directly impacted by different types of resources extraction.” She pointed out that the strategy of community people is quite different of that of big NGO’s. “There are many, many frontline communities that are directly impacted by different types of resources extraction.” She added “I speak here today as an Indigenous person who works on these issues, but I do not consider myself an environmentalist. I am an Indigenous person working to protect our Diné lands and culture.” She went on explaining in which ways the environmentalists differ from Diné people: “The perspective of many environmentalists is to separate themselves from the environment, but we view the Earth as our Mother and coal is the liver of our Mother, we are protecting the Earth as a living, breathing entity. So, we are part of the Earth, we are from the land, so we consider the elements and places on the land as sacred. We consider coal as the liver of our Mother, water is like her blood, and the same goes for uranium, it is also a part of our Mother and should not be taken out but left in the ground. The place where I come from is also being impacted by a lot of fracking. Some of you may know of Chaco canyon, it is also a place impacted by fracking.”

Uranium mining in Navajo Land

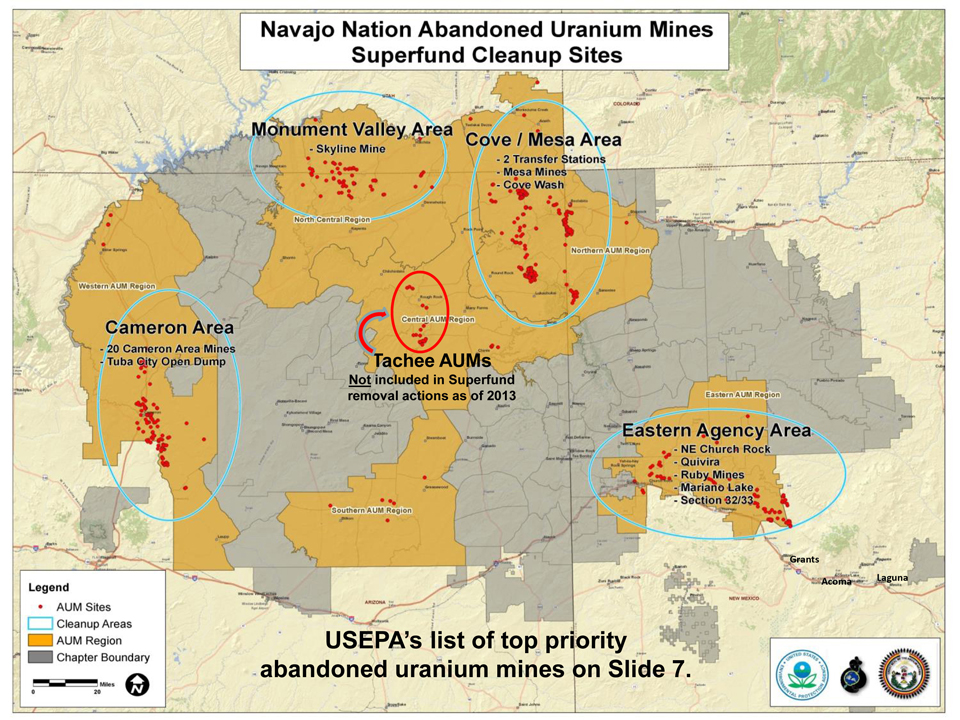

“I shall look into uranium mining now. Just keep in mind where there is uranium mining in my people’s land there is also coal and fracking as well. How many of you are aware of the uses of uranium? Do you understand what uranium is used for? [They all raise their hands]. Sometimes people do not understand that uranium is used for both weapons, which is for imperialism and oppression, and the energy, now also a big issue because of climate change. And we know this year is a big year because it is the 75th anniversary of the first nuclear weapon test and the two nuclear bombs that were dropped in Japan. The first nuclear weapon test was in New Mexico on July 16th 1945. I live in New Mexico and my family has been in New Mexico for many, many generations. The country that have the most uranium is Australia. And this is where the uranium is in the United States. So, my people live here, in this region, this is Arizona and this is New-Mexico. And you can see there is uranium in Wyoming, and South Dakota, and Texas as well. The use of uranium from the 1940’s to the 1980’s was mainly for weapons, before nuclear energy, 100% of uranium was for weapons. During the time of the manufacturing of weapons, the United States mined uranium all over the country and did not have any laws to clean up the uranium mines. One of the laws in the 19th century was a mining law that helped to colonize the United States. That law is still used today, and, again, it did not require the cleaning up of the mining. So, today there are over 15000 abandoned uranium mines in the United States. There is over 600 000 abandoned mines of various minerals, but 15000 that are uranium.”

“I shall look into uranium mining now. Just keep in mind where there is uranium mining in my people’s land there is also coal and fracking as well. How many of you are aware of the uses of uranium? Do you understand what uranium is used for? [They all raise their hands]. Sometimes people do not understand that uranium is used for both weapons, which is for imperialism and oppression, and the energy, now also a big issue because of climate change. And we know this year is a big year because it is the 75th anniversary of the first nuclear weapon test and the two nuclear bombs that were dropped in Japan. The first nuclear weapon test was in New Mexico on July 16th 1945. I live in New Mexico and my family has been in New Mexico for many, many generations. The country that have the most uranium is Australia. And this is where the uranium is in the United States. So, my people live here, in this region, this is Arizona and this is New-Mexico. And you can see there is uranium in Wyoming, and South Dakota, and Texas as well. The use of uranium from the 1940’s to the 1980’s was mainly for weapons, before nuclear energy, 100% of uranium was for weapons. During the time of the manufacturing of weapons, the United States mined uranium all over the country and did not have any laws to clean up the uranium mines. One of the laws in the 19th century was a mining law that helped to colonize the United States. That law is still used today, and, again, it did not require the cleaning up of the mining. So, today there are over 15000 abandoned uranium mines in the United States. There is over 600 000 abandoned mines of various minerals, but 15000 that are uranium.”

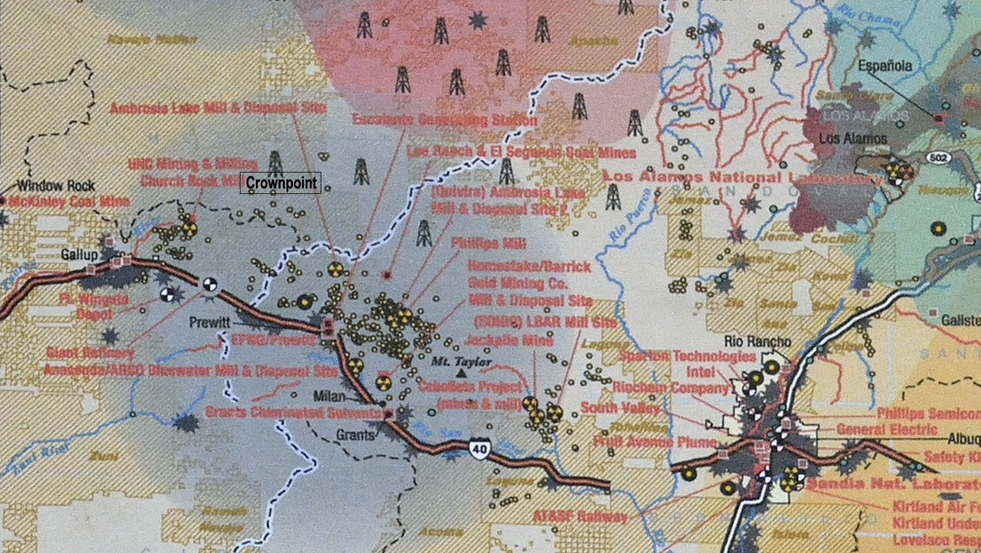

Most uranium mines are in an area between Utah and Colorado, and also in the area in New Mexico around the sacred Mount Taylor, near Grants.

Most uranium mines are in an area between Utah and Colorado, and also in the area in New Mexico around the sacred Mount Taylor, near Grants.

Then, Leona explains that uranium comes from deep in the earth and naturally moves up toward the surface. That happens, of course, in millions of years, but because of mining, it moves more and much quicker. When it is exposed to oxygen, it changes chemically and moves in the environment. When it rains, it can move to places where people live and go into the water ways. Leona, showing a picture, says “This is a mesa, a rock in Monument Valley. This rock is in an area where there was a mine”, “the waste came down the rock and it goes down by houses.”

“On our Navajo Nation, on our people’s land, we have 523 abandoned uranium mines.” The tribal government, working with the federal government, said that they cleaned up about 200 mines.” The work stopped because of lack of funds, cleaning being much more expensive than what they had first thought. Leona: “They tried to find old companies and tried to make them pay. Many of those companies no longer exist, but some companies were bought by bigger companies such as General Electric. So, when the tribe or the federal government find these companies, they try to hold them accountable to pay for some of the old mess. But I learned, about two weeks ago, that 200 or so have been cleaned up, and now they say there is no more money for the other 300.” Leona adds that mining is only one part of the nuclear fuel chain. The second part is processing. “A mill is much dirtier than a mine, because it is where they use chemicals to separate the uranium from the rock.” Nowadays, there is only one uranium mill still operating in the United States, in South Utah, on the land of the community of Ute Mountain Utes.

“On our Navajo Nation, on our people’s land, we have 523 abandoned uranium mines.” The tribal government, working with the federal government, said that they cleaned up about 200 mines.” The work stopped because of lack of funds, cleaning being much more expensive than what they had first thought. Leona: “They tried to find old companies and tried to make them pay. Many of those companies no longer exist, but some companies were bought by bigger companies such as General Electric. So, when the tribe or the federal government find these companies, they try to hold them accountable to pay for some of the old mess. But I learned, about two weeks ago, that 200 or so have been cleaned up, and now they say there is no more money for the other 300.” Leona adds that mining is only one part of the nuclear fuel chain. The second part is processing. “A mill is much dirtier than a mine, because it is where they use chemicals to separate the uranium from the rock.” Nowadays, there is only one uranium mill still operating in the United States, in South Utah, on the land of the community of Ute Mountain Utes.

The Church Rock Disaster in 1979

Then, Leona talked about the Church Rock disaster, the biggest nuclear disaster in the history of the United States, although it got very little press coverage, as compared to the Three-Miles-Island accident, which happened the same year. “On July 16th, the same day as the Trinity test, but in 1979, there was an accident at this uranium mill.” There were two uranium mines there, which had been operated from the 1950’s to the late 1970’s, early 1980’s. The uranium ore was processed in the mill nearby. The mill produced waste, the liquid waste being stored in a tailings pond. “The tailings pond was closed by a dam that was made of clay, to keep the water inside of the dam. The dam had a crack in it, the company knew this, but they kept putting in more and more waste. About 5.30 in the morning, on July 16th, the dam broke. More than 90 million liquid gallons of radioactive waste flowed out of the tailings pond. It went into this little ditch. The river was dry, there was no water. When the water came from the tailings pond, it got into the river and flowed over 100 miles into Arizona.”

Then, Leona talked about the Church Rock disaster, the biggest nuclear disaster in the history of the United States, although it got very little press coverage, as compared to the Three-Miles-Island accident, which happened the same year. “On July 16th, the same day as the Trinity test, but in 1979, there was an accident at this uranium mill.” There were two uranium mines there, which had been operated from the 1950’s to the late 1970’s, early 1980’s. The uranium ore was processed in the mill nearby. The mill produced waste, the liquid waste being stored in a tailings pond. “The tailings pond was closed by a dam that was made of clay, to keep the water inside of the dam. The dam had a crack in it, the company knew this, but they kept putting in more and more waste. About 5.30 in the morning, on July 16th, the dam broke. More than 90 million liquid gallons of radioactive waste flowed out of the tailings pond. It went into this little ditch. The river was dry, there was no water. When the water came from the tailings pond, it got into the river and flowed over 100 miles into Arizona.”  The area is still contaminated. In July 2015, a Navajo scholar, Tommy Rock, in the course of his research, found out that the drink water of a Navajo community in Sanders, at the border between Arizona and New Mexico, was radioactive. Exceptionally, the Rio Puerco had water in 2015. The area of the old mill had been watched by the EPA, but the water of the river had never been studied.

The area is still contaminated. In July 2015, a Navajo scholar, Tommy Rock, in the course of his research, found out that the drink water of a Navajo community in Sanders, at the border between Arizona and New Mexico, was radioactive. Exceptionally, the Rio Puerco had water in 2015. The area of the old mill had been watched by the EPA, but the water of the river had never been studied.

Fighting uranium mines since 2007

Leona started her work with fighting a new uranium mine in 2007. The new mine was to be situated near where her family lives. [Crownpoint, see map below]. The company claimed they were going to use a new type of mining called ‘In situ leaching’. Uranium ore found in aquifers does not dissolve naturally. Thus, this process means injecting chemicals (poisonous too) into the aquifer to loosen the uranium. Then, they pump and filter the water to get the uranium. Of course, the water they leave in the aquifer is radioactive. People had been fighting against the project for some time, Leona got involved in 2007, when she was a student. They were lucky to manage to stop the project. (However, people usually manage to stop uranium mining projects when the price of uranium on the world market is low. Many mines which got a permit to start extracting uranium are still waiting for the price to go up). Still, Leona is optimistic about that victory, she says “Our belief is that if we can stop uranium mining, we can also stop nuclear weapons and nuclear energy.” But she pointed out that even after cleaning up, the land is never the same. And, those changes affect their entire way of life. In the Church Rock community, sheep have been affected too, and Navajos eat a lot of sheep meat. Diné students are doing studies about the effects of the contamination and recommend to eat only the meat, but not the organs – which used to be quite common, and delicious! “So, you can see this issue spans not only the environment but food sovereignty as well as reproductive justice and so many issues.”

Leona’s work with Radiation Monitoring Project

Leona thus started a project called “Radiation Monitoring Project”, which is mainly an educational project. She says “Part of the work I do is mostly popular education.” The group had to gather data and make pictures on how radiations get in people’s body. Radiations mostly impact women and children, most of all the unborn children.  For the ‘Radiation Monitoring Project’, they raise money to buy Geiger counters which people can borrow for as long as they need, to measure the radiations in their community. The training they give is designed for each community, according to their needs. Some communities are impacted by uranium mines, others by nuclear reactors or a uranium mill. They provide education and tools at no cost.

For the ‘Radiation Monitoring Project’, they raise money to buy Geiger counters which people can borrow for as long as they need, to measure the radiations in their community. The training they give is designed for each community, according to their needs. Some communities are impacted by uranium mines, others by nuclear reactors or a uranium mill. They provide education and tools at no cost.

Fighting the whole nuclear cycle

“We talked a lot about the past mining that was used for weapons, but now there are many, many new threats from the nuclear cycle.” Leona showed a picture of the Navajos’ sacred mountain of the south, Mount Taylor, Tsoodził in Diné. The

“We talked a lot about the past mining that was used for weapons, but now there are many, many new threats from the nuclear cycle.” Leona showed a picture of the Navajos’ sacred mountain of the south, Mount Taylor, Tsoodził in Diné. The  mountain is sacred to all local Indigenous Peoples. The Acoma who live nearby call it ‘Kaweshti’. They are one of the closest communities to the mountain. They depend on it for the water that comes down from it. The area is full of abandoned mines. At the moment, there is no uranium mining in New Mexico, but there are proposals for two uranium mines on Mount Taylor. [At a time, AREVA was involved]. Another proposal for mining at a sacred site is the Canyon Mine, in Arizona, near the Grand Canyon. The company at Canyon Mine, Energy Fuels, also has a project called Roca Honda, at Mount Taylor.

mountain is sacred to all local Indigenous Peoples. The Acoma who live nearby call it ‘Kaweshti’. They are one of the closest communities to the mountain. They depend on it for the water that comes down from it. The area is full of abandoned mines. At the moment, there is no uranium mining in New Mexico, but there are proposals for two uranium mines on Mount Taylor. [At a time, AREVA was involved]. Another proposal for mining at a sacred site is the Canyon Mine, in Arizona, near the Grand Canyon. The company at Canyon Mine, Energy Fuels, also has a project called Roca Honda, at Mount Taylor.

The ‘Haul NO!’ campaign

In 2015, anti-nukes activists started a campaign called ‘Haul NO!’. For Americans, it sounds as ‘Hell, NO!’ The campaign was about the transport of uranium from Canyon Mine to the processing mill in Utah, through the Navajo Nation. Leona said “We worked together with the different Indigenous peoples in this campaign. It is an Indigenous led fight with support from many non-Indigenous allies, supporters and other folks.” The focus of the campaign was to create awareness and action.

In 2015, anti-nukes activists started a campaign called ‘Haul NO!’. For Americans, it sounds as ‘Hell, NO!’ The campaign was about the transport of uranium from Canyon Mine to the processing mill in Utah, through the Navajo Nation. Leona said “We worked together with the different Indigenous peoples in this campaign. It is an Indigenous led fight with support from many non-Indigenous allies, supporters and other folks.” The focus of the campaign was to create awareness and action.  They started at the mill in Utah. They stopped at communities and did workshops on the way. Many people became aware of the problem because of the campaign. The company claimed that they were not moving any uranium, but the activists managed to catch them. They also managed to make a video showing the reality of what was happening at Canyon Mine:

They started at the mill in Utah. They stopped at communities and did workshops on the way. Many people became aware of the problem because of the campaign. The company claimed that they were not moving any uranium, but the activists managed to catch them. They also managed to make a video showing the reality of what was happening at Canyon Mine:

They got support from the Sierra Club, but the company did not get in trouble. “The government agency changed the permit to include this.” The mine is only 6 miles away from the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai community, which lives in the Grand Canyon, depend on the water coming down and fear that the sources are contaminated. They also have their sacred site, Red Butte, 4 miles away from the mine. They also use the place and the water sources for ceremonial purpose.

They got support from the Sierra Club, but the company did not get in trouble. “The government agency changed the permit to include this.” The mine is only 6 miles away from the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai community, which lives in the Grand Canyon, depend on the water coming down and fear that the sources are contaminated. They also have their sacred site, Red Butte, 4 miles away from the mine. They also use the place and the water sources for ceremonial purpose.

THE WIPP AND WCS

The WCS is a dump for less radioactive waste, in Texas, on the border with New Mexico. The company wants to build a new waste dump there to take about half of the reactors waste in the United States.  The WIPP is a Waste Pilot Project. Now, the biggest fight is against a company called Holtec. They are trying to build a dump for much more waste. Holtec buy waste to be recycled or enriched to make money out of it. The authorities of New Mexico are against dumps, but friends of the company are trying to change the law in Congress. New Mexico only has two Senators and three Representatives in Congress, which means very little political power. However, opponents have a national network of activists working together. What happens in the United States and many other countries with nuclear energy, is that there is a lot of very dangerous waste and nowhere to put it.

The WIPP is a Waste Pilot Project. Now, the biggest fight is against a company called Holtec. They are trying to build a dump for much more waste. Holtec buy waste to be recycled or enriched to make money out of it. The authorities of New Mexico are against dumps, but friends of the company are trying to change the law in Congress. New Mexico only has two Senators and three Representatives in Congress, which means very little political power. However, opponents have a national network of activists working together. What happens in the United States and many other countries with nuclear energy, is that there is a lot of very dangerous waste and nowhere to put it.  Leona then talked about her visit to Bure, on invitation from Pascal Grégis, member of the CSIA, as well as her visits to German friends also fighting nuclear waste. She says “The thing we all need to work on, I think, is to stop making nuclear waste, stop making nuclear weapons, stop making nuclear energy, stop uranium mining, and this will require a lot of working together.” Unfortunately, there are now many divisions in the fight, the weapons fight is separate from the energy fight. Moreover, “As Indigenous Peoples we are also dealing with racism and other issues when we talk about nuclear colonialism.”

Leona then talked about her visit to Bure, on invitation from Pascal Grégis, member of the CSIA, as well as her visits to German friends also fighting nuclear waste. She says “The thing we all need to work on, I think, is to stop making nuclear waste, stop making nuclear weapons, stop making nuclear energy, stop uranium mining, and this will require a lot of working together.” Unfortunately, there are now many divisions in the fight, the weapons fight is separate from the energy fight. Moreover, “As Indigenous Peoples we are also dealing with racism and other issues when we talk about nuclear colonialism.”

One issue is climate change. Western leaders and companies claim that nuclear energy is carbon free, which is not true. “They only count the carbon from the reactor, and they say ‘oh it’s just steam, there is no carbon’. They don’t count the mining, the milling, the enrichment, and all the steps that make the fuel. They don’t count the transport, and they don’t count the waste storage, which is radioactive for millions of years.”

As a conclusion, Leona said that we have to figure out a way to push changes. This can only be achieved by knowing the problems, and knowing and educating the impacted communities.

“We need to support one another in solidarity and to unite our fight all together. And, very important is to respect each other’s culture. I think that when we work together, we might understand one another and this can be done by sharing our stories. For the protection of sacred sites, the protection of water, the protection of life, for our future generations.”